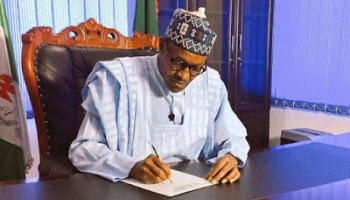

September 30th, his self-imposed deadline for finally announcing his Cabinet after four months in office, Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari simply said that he would run the oil ministry himself. Buhari would appoint someone else to run day-to-day operations of the ministry, but he would direct the national oil portfolio rather than let it be further mismanaged. His declaration had an unfortunate dictator-like tone, coming from a former military dictator, but the timing was apt. Two days later, former oil minister Diezani Alison-Madueke, who left office in March along with the rest of former President Goodluck Jonathan’s Cabinet, was arrested in London by Britain’s National Crime Agency on suspicion of bribery and money laundering. The agency’s International Corruption Unit also arrested four others; all five were released on conditional police bail that night. Alison-Madueke reportedly had forty-one thousand dollars on her when she was apprehended, which the National Crime Agency temporarily seized last Monday. In her five years as oil minister, she has been implicated in the graft of billions of missing oil dollars in Nigeria. (Last weekend, Alison-Madueke’s lawyer issued a statement saying that she was not arrested or detained, and only spent forty-five minutes with British police.)

Alison-Madueke, who was educated at Howard and Cambridge, and formerly served as an executive director for Shell’s operations in Nigeria, was best known for her ability to escape censure while the ministry she ran imploded. Two incidents stand out. First, there was a scam involving the country’s fuel subsidy, in which oil importers were paid for fifty-nine million liters a day, while only thirty-five million liters were used domestically. Some so-called oil importers didn’t actually import oil at all but took money for nonexistent fuel. The scheme is said to have cost Nigeria nearly seven billion dollars from 2009 to 2011. In 2014, the governor of the Central Bank of Nigeria, Lamido Sanusi, revealed that up to twenty billion dollars in oil revenue had gone missing between the government-run oil company and the Central Bank. Jonathan, then the President, responded by firing Sanusi, as Alison-Madueke denied any wrongdoing.

Not long after he was elected, Buhari vowed to go after former government officials who had stolen money and to recover the funds—he estimated a hundred and fifty billion dollars over the last decade—but this arrest was quicker than expected. It’s unclear what Buhari’s government knew about the arrest before it happened, but Max Siollun, a Nigerian military historian and political analyst, told me in an e-mail that it’s “extremely unlikely that a high-profile figure like Madueke would be arrested without the prior consent or foreknowledge of the Nigerian government.” Siollun went on, “Buhari needs a ‘big catch’ to reinforce his anti-corruption credentials (part of why he was elected). A high-profile minister from the former government of President Jonathan will be made an example of.” Soon after her arrest in London, Alison-Madueke’s home in Abuja was searched and sealed by Nigeria’s Economic and Financial Crimes Commission. On October 4th, Buhari’s office said that “all the government investigative agencies are working very closely with the British law enforcement.”

It is true Buhari has had experience managing Nigeria’s oil assets, and could probably do better than Alison-Madueke: he was oil minister in the nineteen-seventies and manager of the petroleum trust fund in the nineteen-nineties, under the military ruler Sani Abacha. But the partial list of his Cabinet nominees, which he released to parliament last Tuesday, is disappointing. Buhari chose party loyalists—like the spokesman of his All Progressives Congress, Lai Muhammed—as well as politicians such as former Lagos Governor Babatunde Fashola, who has been accused of misusing state funds. (He denies all of the accusations.) The average age of the nominees was in the mid-fifties; there were three women among the twenty-one nominees.

It is difficult to eschew patronage networks in Nigeria—Buhari himself was partly elected on the strength of an alliance with veteran kingmaker and southwestern politician Bola Tinubu, who was charged with the illegal operation of sixteen foreign bank accounts while he was the governor of Lagos but never convicted. Still, many expected a fresher lineup than this, more in line with the bureaucratic overhaul he promised. “This is a reminder that, although Nigerians elected Buhari on a platform of change, Buhari’s victory was planned by many people who used to be part of the previous government,” Siollun said. “To some extent, the ‘change’ was a rebranding exercise.”

Buhari has taken other, more promising actions. He mandated that all government financial transactions pass through a single bank account so that he can monitor spending, and divided the national oil company into two, firing most of its board and naming a new chief executive. Nigerians of an older generation still speak fondly of Buhari as a man who, despite his authoritarian tendencies, had little tolerance for corruption during his brief run as military rule. It is too soon to tell if that will be enough. The New Yorker