Gordon Rayner

When Tuesday morning dawns in Barbados, British influence in the Caribbean will retreat one more step as the island becomes a republic, ending almost 400 years of loyalty to the Crown.

The Queen will be head of state of one fewer Commonwealth realm, though the transition will be a gentle one, as her replacement, president-elect Dame Sandra Mason, is currently the governor-general, Her Majesty’s official representative.

In truth, however, Barbados has already drifted away from Britain, and in common with dozens of other Commonwealth members it has become increasingly dependent on another international partner: China.

Britain may have the Queen, but China has the cash, and in recent years Beijing has ploughed almost £500 million into the Barbadian economy, which equates to around a tenth of its gross domestic product. Roads, homes, sewers and a hotel have all been constructed with Chinese yuan, not British pounds or US dollars.

The picture is the same in Jamaica, widely expected to be the next Commonwealth realm to become a republic, where £2.6 billion of Chinese investment, against a GDP of £16.4 billion, makes it the biggest recipient of Chinese cash in the Caribbean.

In total, China has invested £685 billion across 42 Commonwealth countries since 2005, according to figures compiled by the American Enterprise Institute. To put that figure in context, Chinese investment in Commonwealth member states is, on average, three times higher as a proportion of the recipient’s GDP than in non-member countries, a Telegraph analysis has established.

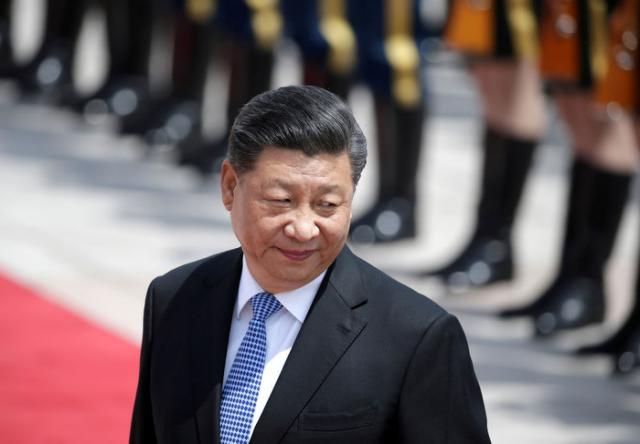

Much has been made by Boris Johnson of the opportunity for increased trade with Commonwealth countries as part of his post-Brexit Global Britain strategy, but the evidence suggests President Xi Jinping was way ahead of him.

On Wednesday Liz Truss, the Foreign Secretary, announced plans to replace the Commonwealth Development Corporation with a new body, British International Investment, which she hopes will provide “up to £8 billion” of investment per year in Commonwealth countries by 2025, up from £1.5 billion per year at the moment, by encouraging the private sector and western allies to put money into member states.

The plans are undoubtedly welcome, but critics wonder why it has taken so long.

“We have been completely asleep at the wheel for decades,” says Didi Kirsten Tatlow, a senior non-resident fellow at the Sinopsis project in Prague, a world-leading resource on China’s foreign policy.

“We fundamentally misunderstood what the Chinese Communist Party is, and what it wanted. We have blundered into this scenario.”

Enter the dragon

From an economic perspective, President Xi made it clear in a speech last year that he wants to “create more opportunities for the world to benefit from China’s high-quality development” – in other words, to be more dependent on China, and in that goal he is having remarkable success.

Economic might, of course, is the most powerful tool in exerting political control, and the consequences of the West allowing China to become the main economic partner for so many countries are far-reaching.

“They are using their considerable financial resources to build strategic dependencies in societies wherever they can,” says Tatlow. “This is how you start to control the world around you and start making it safe for totalitarianism because countries can’t afford to do anything about it.”

When China wanted United Nations members to support its draconian Hong Kong National Security Law – giving it sweeping powers to suppress dissent in the former British colony – it received backing from 53 countries, including two out of the 16 remaining Commonwealth realms: Papua New Guinea and Antigua and Barbuda. Both have received significant Chinese investment: £5.3 billion in the case of Papua New Guinea, or 21 per cent of its GDP, and £1 billion in the case of Antigua and Barbuda, or 60 per cent of GDP.

Other Commonwealth members that supported the Chinese crackdown in Hong Kong, and which have been in receipt of Chinese investment, included Sierra Leone, where Chinese investment since 2005 amounts to 145 per cent of GDP; Pakistan (21 per cent of GDP); Sri Lanka (17 per cent of GDP); Zambia, Lesotho, Cameroon and Mozambique.

Baroness Helena Kennedy, a prominent human rights barrister, says: “What China is doing is a way of making friends and it impacts on votes in the UN. Attempts to get a collaborative approach to things can be undermined so you end up with client states.

“It has a serious impact, it starts being a return to the old Cold War scenario and that’s not a healthy way for us to be going forward.

“The money they are investing does start to penetrate our areas of influence. One wants to strengthen the Commonwealth, not find it undermined.”

Alan Mendoza, executive director of the Henry Jackson Society, a foreign affairs think tank, says China appears to be targeting the Commonwealth because it sees it as “weak”.

He says: “They would like to undermine whatever they can internationally, so they can pick off countries and prevent anti-Chinese resolutions in the Commonwealth and elsewhere. It is a very clever move and we have come late to the party by not really understanding the extent of this challenge.

“China is commercially preying on the Commonwealth. The question is, can we respond with a better offering? Can the UK steer western investment funds into these places?”

Mendoza says the stark statistics on Chinese investment in Commonwealth member states leads to the inevitable question of what the Commonwealth is for.

When Barbados becomes a republic next week, it will remain a member of the Commonwealth, the 54-member association which has expanded during the Queen’s reign and remains one of her proudest achievements.

The danger, though, for British diplomacy is that a future president of Barbados could decide to leave the Commonwealth and build new alliances elsewhere.

“Is the Commonwealth a group of states working together or just a random collection of states that has no future?” Mendoza asks.

“Richer members of the Commonwealth should be the lead investors in the poorer member countries, but instead it’s China. Surely this is the time to tackle the subject, or are we just going to allow the Commonwealth to become a relic?”

A modern-day Silk Road

In Jamaica the projects financed by China include a new 41-mile toll road from the capital, Kingston, to the north coast’s tourist resorts. A journey which used to take two hours now takes just 50 minutes, thanks to Beijing.

Across the Caribbean, China has given equipment to military and police forces, including coastal patrol vessels, as well as building a network of Confucius Institutes (including one at the University of the West Indies in Barbados) which offer Mandarin language classes but have been accused of spreading Chinese propaganda. Covid has also been used as an opportunity to ship test kits, masks and ventilators to help combat the pandemic.

Caribbean nations are not, on the whole, rich in the minerals or natural resources that China seeks elsewhere, but they are coveted by Beijing because they lie so close to America. Beijing has long been upset by US military dominance in the Pacific and any Chinese leverage in the Caribbean is seen as one in the eye for Washington. In the long term, China may even have military ambitions in the area, though we are a long way from anything resembling the former Soviet Union/Cuba alliance.

The Chinese Communist Party is also determined to win over nations that recognise Taiwan as a sovereign nation, many of which are in the Caribbean and Latin America.

Rasheed Griffith, a senior fellow at the Inter-American Dialogue think tank who specialises in China’s presence in the region, says Britain is guilty of a failure of diplomacy as well as failing to provide financial help to its allies.

He says: “The UK has abrogated foreign policy in the Caribbean; their foreign policy is simply performance art. There is nothing happening; they don’t know what’s going on, they don’t do anything, the embassies don’t actually know much about the Caribbean any more.”

On the other side of the world, Commonwealth member Pakistan, which is the biggest recipient of UK Overseas Development Assistance, to the tune of £305 million in 2019, is also being targeted by China. Since 2005 it has received £60 billion of investment from China, more than a fifth of its GDP, and it now buys 70 per cent of its arms from China.

The US believes Pakistan passes on some of those arms to the Taliban, which used them to defeat the coalition forces in Afghanistan. And the resulting destabilisation of the Afghan economy provides opportunities for China to move in and exhaust the country’s vast mineral deposits, which include coal, copper, iron ore, lithium, uranium, gold, oil and gemstones. Chinese money comes in the form of straightforward investment – buying land and building hotels, for example – but also in the form of loans, which are by no means risk-free for the nations that accept them.

If recipient countries cannot afford to repay what are often high interest loans, China will simply seize the assets that have been used as security.

In Sri Lanka, for example, when the government became unable to make payments on a loan it had taken out to build the Hambantota container port, it was forced to hand over the port and 15,000 acres of land around it to Beijing on a 99-year lease.

Although the port is likely to remain loss-making, it gives China a strategic foothold in a critical shipping channel off the coast of a rival nation, India.

Critics call this “debt trap diplomacy”, and Ms Truss is well aware of the problem.

“Too many countries are loading their balance sheets with unsustainable debt,” she said this week. “Reliable and honest sources of finance are needed. Britain and our allies will provide that.” But China will provide more.

China calls it the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), its somewhat enigmatic name for the global infrastructure development strategy brought in by President Xi in 2013.

Sometimes referred to as a modern-day Silk Road, it includes investment in around 70 countries with roads, railways, ports, airports, power stations, hotels and other buildings among the panoply of real estate taking shape.

The Belt refers to the economic belt through Central Asia to Europe, while the Road refers to the Silk Road element.

Put simply, it is Xi’s policy of using China’s vast cash reserves to gobble up raw materials, form political alliances and dominate global trade long into the future.

The challenge for the West

Commonwealth countries would far rather borrow from Britain or other western countries, but they complain that the investment they need simply isn’t available from more natural allies.

Biyika Lawrence Songa, an MP in the Parliament of Uganda, a member state which has had almost £9 billion of Chinese investment, says: “Commonwealth countries, including Uganda, are running to China instead of Britain or other countries, because it is very easy to access Chinese money and it is easy for our businessmen to get Chinese visas if they want to go there to buy materials, for example.

“In contrast, there are lots of conditions attached to loans from European or American countries and visas are harder to get.”

He says the UK and Europe “must address the challenges that have driven Commonwealth countries to China. It is because of a lack of alternatives that this has happened”.

Andreas Fulda, a China scholar and associate professor in social sciences at Nottingham University, adds: “In the case of Africa, the UK has taken its eye off the ball and has given Africa insufficient attention, and that has given China an opening that wouldn’t otherwise exist.

“If you don’t invest and if you don’t have a forward-looking foreign policy other players will fill the gap.

“It’s in the G7’s self interest to re-engage with these countries because otherwise China can use its economic heft to buy its way in.”

The US, Japan and Australia tried to counter it with their own Blue Dot Network in 2019, followed by the G7’s Build Back Better World agreement earlier this year, essentially a western version of BRI, but China has such a head start that it may be too late for the West to catch up. Indeed, the West is suckling at the teat of China’s cash reserves just as poorer nations are doing.

Chinese investment in the UK since 2005 amounts to £98.6 billion, some 0.03 per cent of GDP, though the more pertinent fact is the extent to which the West has been happy to rely on China for its manufacturing needs.

Almost all of us have a mobile phone, laptop, television, electric car, toys, almost anything you care to name, that was made in China, and western firms continue to flock there to build factories that provide cheap labour.

A report by Parliament’s business select committee earlier this year warned that Uyghur Muslims from Xinjiang in northwest China were being used as “slave labour” in factories all over the country. The report said companies that were “directly or indirectly benefiting from the exploitation of Uyghur workers” included Adidas, Amazon, Apple, Google, Jaguar, Land Rover, Nike, Samsung, Uniqlo, Victoria’s Secret and Zara.

Fulda says: “It’s quite a messy picture – it’s not a case of big bad China versus the ethical West; it’s all intertwined.

“British companies are heavily invested in China in terms of global supply chains and the West is partially responsible for what we see in China. Some sort of partial decoupling would be needed to reverse this – for example don’t build factories in Xinjiang.”

Sir Iain Duncan Smith, the former Conservative leader and a member of the Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China (IPAC), says: “China has strategically made sure that we have to rely on them in key areas, like making electric cars.

“The answer is to start shifting our investments from China to countries like India. We need to stop buying Chinese goods and we need to look to other places to make things.”

Paul Flather, a fellow of Mansfield College, Oxford, adds: “We need to put a brake on China, and the Commonwealth could do that. This is a chance for the Commonwealth to test itself. It can’t continue to be a diminishing historical legacy; it needs to recognise its role and if it’s going to be influential, it needs to step up.”

Democracies, with their ever-changing governments, tend to prioritise short-term gains, whereas, says Flather: “China has a permanent government and now an almost permanent leader… it’s able to think long-term.”

As to whether the Commonwealth has a future, Songa says: “That is a very good question. Countries are bypassing the Commonwealth and although they are Commonwealth members by name there is nothing coming from the Commonwealth to help these countries. Where is that wealth that is common to us?

“Europe and America are now realising there is a problem. But it’s a bit late.”

A Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office source said that Ms Truss thinks that by investing more overseas we can draw more countries into the orbit of freedom-loving democracies while also improving lives, so it’s very much a positive agenda”.

A spokesman for the department said Ms Truss’s plans for extra finance, called British International Investment, would provide “honest, responsible investment to create new markets in Africa, the Caribbean and the Indo Pacific” by partnering with capital markets and sovereign wealth funds “to co-invest in projects and scale the offer further”.

As well as having “high standards, transparency and reliability” the BII plan would create jobs in the UK by generating export opportunities in countries that were being helped.

The West has finally woken up, but China’s challenge is changing

By Tom Tugendhat MP, Chair of the Foreign Affairs Select Committee

There was a week in 2019 which should have set alarm bells ringing. In the space of just four days, Kiribati and the Solomon Islands both announced that they were immediately severing diplomatic ties with Taiwan and switching allegiances to Beijing. These two tiny Commonwealth island nations are both about 5,000 miles from Beijing. Welcome to the new era of global China.

The seeds of that diplomatic win for Beijing were sown a decade ago. From 2008 to 2009, China’s two biggest lending banks went from overseas lending of £7.5 billion to over £45 billion almost overnight. Roads, bridges and railways sprang up across Africa, the Caribbean and the South Pacific.

By the time Xi launched the One Belt One Road – now known as the Belt and Road (BRI) – in 2013, China’s expansion of overseas lending was already well under way. From Dhaka to Darfur, governments loaded themselves up with debt in exchange for the infrastructure they desperately needed.

But the reality is that many recipients of this flow of cash signed up to bad deals. In too many cases, Beijing cosied up to corrupt leaders, loading up their countries with debt on opaque terms under contracts laden with confidentiality clauses.

That is why we are in a situation where Zambia’s new government has just confirmed that the country actually owes more than £4.5 billion to China – double what the previous government claimed. For a country with a GDP of £14 billion, that is a striking difference.

It’s not surprising that in many Commonwealth countries, the opacity of the debt and the poor environmental and labour standards on those projects have triggered backlash. The current riots in the Solomon Islands are at least partly a protest against extractive arrangements with Chinese businesses. Kenya abandoned plans for a huge new Chinese-built coal plant after staunch local opposition in Lamu. And Nigerian MPs have voted to review all of its Chinese loans.

We can’t blame the Commonwealth countries. The UK and the rest of the West seem to have taken the last decade off. There were no better alternatives.

The good news is that we have belatedly woken up. Our allies, Japan and Australia, have stepped up their game in the Indo-Pacific, and the US is on a mission to revive its influence in Africa and Asia.

But the challenge of China’s investment is also changing. We are now in the era of BRI 2.0. In the wake of the pandemic, Chinese leaders appear to be trying to reset. Lending for infrastructure has collapsed. Kenya’s feted high-speed railway, from the port of Mombasa to Uganda, was meant to be a headline BRI megaproject but now it lies unfinished, 300 miles short of its destination, after the project ran out of cash. Beijing is embroiled in debt renegotiations with at least 18 African countries.

In the face of this debt disaster, Beijing is pivoting. The BRI is being rebranded as the Digital Silk Road. Beijing has pledged to kit out the world with 5G networks and datacentres.

We should be wary, because this creates a new set of risks. Building Africa’s digital infrastructure creates a stronger lock-in effect than physical infrastructure. Anyone can build a bridge, but not everyone can build a 5G system that works alongside Huawei. And technology also makes it much easier to export a brand of digital authoritarianism which China has implemented at home.

The Commonwealth needs sustainable infrastructure and investment. We can’t compete with China on the sheer amount of capital, but we can compete on transparent lending and inclusive growth. The UK needs to work with allies to ensure that Commonwealth countries have a genuine alternative to China’s deep pockets. The British International Investment (BII) announced on Wednesday will be a good start if it doesn’t just rebrand the Commonwealth Development Corporation, but builds on it, and brings in new partners.

That’s the challenge we need to take on. The world deserves to be able to choose to invest in freedom, not be forced to take Beijing’s controlling cash. The Telegraph