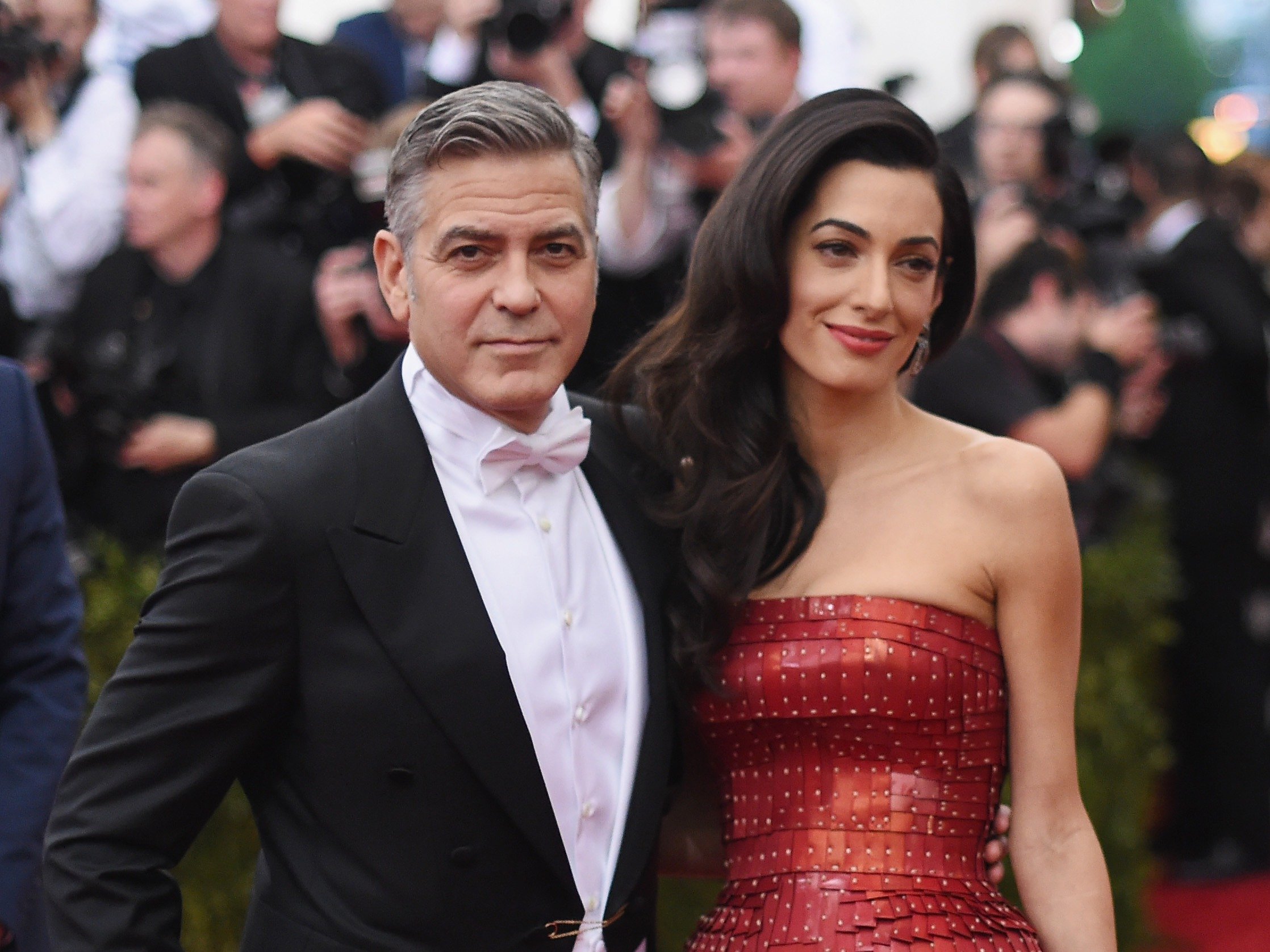

(Getty Images/Mike Coppola)

George Clooney and Amal Alamuddin.

Research suggests that being in a happy marriage is one of the best things you can do for yourself.

According to The New York Times, “being married makes people happier and more satisfied with their lives than those who remain single — particularly during the most stressful periods, like midlife crises.”

Of course, some marriages are more successful than others. The Times’ Tara Parker-Pope recently examined research on the “ambivalent marriage” — one that is “not always terrible, but not always great” — which found that such a partnership can take a toll on health.

So how can you pick the right partner and set yourself up for long-term success?

We asked Peter Pearson, a couples therapist and cofounder of the Couples Institute in Menlo Park, California.

Chemistry was his first answer.

“Chemistry is not everything,” he said, “but if the chemistry is not there, that’s a tough thing to overcome. If the chemistry is more there for one person than the other, that’s tough to overcome. It’s hard to build passion if it’s low at the beginning. If I could find a way to build passion where passion was low, I’d be richer than Bill Gates.”

But it’s not just sexual chemistry, Pearson said. What you might call social chemistry plays a crucial role — the way you feel when you’re with the other person. In his experience, when people have affairs, it’s more than simple lust — it’s also about the way they feel when they’re around the other person.

That sense of “how I feel” can be investigated further by looking at the work of Canadian psychologist Eric Berne. Back in the 1950s and ’60s, Berne developed “transactional analysis,” a model that tried to provide an account of how two people in a relationship interact, or transact.

His popular books about the model became best sellers, namely “The Games People Play.” Drawing somewhat on Sigmund Freud, his theory argued that every person has three “ego states“:

• The parent: What you’ve been taught

• The child: What you have felt

• The adult: What you have learned

When two people are really compatible, they connect along each tier. Pearson gave us a few questions for figuring out compatibility at each level:

• The parent: Do you have similar values and beliefs about the world?

• The child: Do you have fun together? Can you be spontaneous? Do you think your partner’s hot? Do you like to travel together?

• The adult: Does each person think the other is bright? Are you good at solving problems together?

While having symmetry across all three is ideal, Pearson said that people often “get together to balance each other.” One person might identify as fun-loving and adventurous, while the other takes on the role of being nurturing and responsible.

While that divvying up of roles makes for good odd-couple romantic comedies, it’s not ultimately sustainable.

“That works until someone gets tired,” Pearson said — until one partner is shouting, “I’m tired of being the responsible person here!”

When that happens — or, ideally, before that happens — a couple has to go through the “differentiation” process.

Ellyn Bader, Pearson’s wife and Couples Institute cofounder, described in an interview with The Script how the high-tension phase of differentiation works:

People have to come to terms with the reality that “we really are different people. You are different from who I thought you were or wanted you to be. We have different ideas, different feelings, different interests.”

Differentiation has two components. There is self-differentiation: “This is who I am and what I want.” This refers to the development of an independent sense of self: to know what I want, think, feel, desire. …

The second involves differentiation from the other. When this is successful, the members of the couple have the capacity to be separate from each other and involved at the same time.

For couples to survive that differentiation process and maintain their compatibility, the real secret sauce is effort.

But despite all these theoretical models, Pearson said that the clues about what predicts true compatibility are more of a felt sense than something you reason out.

He provided a litmus test.

“If you’re living together and your partner is away for a couple days and you see a favorite scarf, a pair of shoes, or another article of clothing that’s important to them, how do you feel?” Pearson asked. “Do you feel annoyed that you have to pick up the clutter, or does it bring up happy memories?”

The answer can tell you a lot about how your parent, child, and adult are getting along with theirs.

This is an updated version of an article that was previously published