In Nigeria, billions of dollars each year flow illegally from public coffers into private hands. Nigeria’s kleptocracy undermines the regime’s ability to combat Boko Haram, a deadly terrorist movement that has displaced two million people in the country’s war-ravaged northeast.

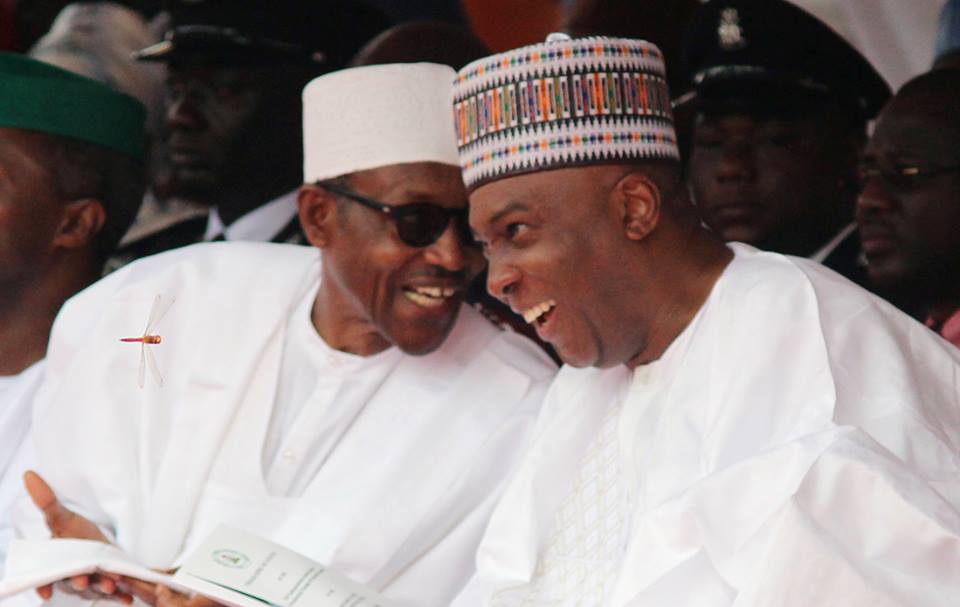

In a new Council on Foreign Relations corruption brief, “Improving U.S. Anticorruption Policy in Nigeria,” I argue that the United States could help deter corruption in Africa’s largest economy and most populous country. Following Muhammadu Buhari’s 2015 presidential election victory, senior U.S. policymakers saw an opportunity to support his aggressive anti-corruption efforts. Thus far, U.S. efforts have consisted mostly of modest assistance programs for police investigators and civil-society watchdogs.

Here’s the problem, from a policy perspective: Corruption is treated as a secondary, stand-alone issue. In fact, corruption is a potent threat to Washington’s efforts to support socioeconomic development, tackle security issues and improve governance in Nigeria.

Corruption isn’t new in Nigeria.

Systemic corruption threatens democracy and good governance in Nigeria. In “This Present Darkness: A History of Nigerian Organized Crime,” the late Stephen Ellis quotes Abubakar Tafawa Balewa in 1950 decrying “the twin curses of bribery and corruption which pervade every rank and department” of government. The Nigerian League of Bribe Scorners, a civil-society organization at the time, likewise complained that “bribery with its allied corruption is deeply planted in this country.” Tafawa Balewa, who became Nigeria’s first post-independence prime minister in 1960, was later assassinated in a coup planned by five officers who claimed Nigeria’s civilian government was too corrupt.

Over the next six decades, corruption thrived under both civilian and military-led governments, implicating leaders of all ethnic and religious affiliations. Yet official corruption rose to new heights under Buhari’s predecessor, President Goodluck Jonathan. Corruption in the security, petroleum and power sectors was particularly prolific. Jonathan’s national security adviser, for example, is on trial for his role in diverting more than $2 billion in security funds while poorly armed government troops battled against Boko Haram terrorists.

For comparison, U.S. military and police aid to Nigeria totaled $45.4 million from 2010 to 2014, according to Security Assistance Monitor.

Graft is prevalent throughout the economy — and government.

Corruption is endemic in the petroleum and power sectors, the two chief drivers of the Nigerian economy. The state-run Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation has long been corrupt and mismanaged, according to the Natural Resource Governance Institute. Though the government has spent $14 billion since 1999 to develop a modern power sector to serve all of Nigeria’s 183 million people, growth in the national electricity supply has been sporadic. Nigeria can generate enough power to meet the needs of a population of just half a million — similar to that of the city of Edinburgh.

The Economic and Financial Crimes Commission, Nigeria’s main anti-corruption body, is actively investigating dozens of sitting and former officials. The country’s senate president is currently standing trial for false asset declaration and other corruption-related charges. At least five former governors are facing trial for graft. And several senior election officialsallegedly accepted millions of dollars in bribes, posing a threat to the integrity and credibility of Nigeria’s elections.

Stronger anti-corruption tools are needed.

Given the scope and scale of Nigeria’s corruption and the threat it poses to specific areas where Washington devotes considerable time and resources — security, development and governance — stronger anti-corruption policies could be a force multiplier, amplifying the impact of U.S. assistance to Nigeria. I argue that three quite feasible policy actions could achieve this: establishing an inter-agency working group on Nigerian kleptocracy, stationing an FBI investigator in the capital, Abuja, and promulgating an executive order restricting financial transactions by corrupt Nigerian officials and freezing, or even seizing, their assets.

These steps could significantly reduce illicit financial outflows from Nigeria, estimated at more than $178 billion from 2004 to 2013, according to Global Financial Integrity. Without a dedicated FBI investigator at the U.S. Embassy, for example, deepening bilateral cooperation on corruption cases will be difficult. But tougher scrutiny of Nigerian transactions into U.S. accounts will help discourage kleptocratic behavior from Nigerian officials.

Matthew T. Page is an international affairs fellow with the Council on Foreign Relations. He is the coauthor of “Nigeria: What Everyone Needs to Know,” forthcoming from Oxford University Press in 2017. Previously with the Department of State’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research, Page was one of the U.S. intelligence community’s top experts on Nigeria.

Photo above: People stand to meet musician Ado Dahiru Daukaka at his home after his release in Yola, in northeastern Nigeria, on June 30. A popular musician, Daukaka was kidnapped days after releasing a scathing anti-corruption song but was freed on June 29, he told AFP. (Randy Haniel/AFP/Getty Images)