Botha’s long career straddled both the apartheid era and Mandela’s government, his death provoked mix reactions.

![South Africa's apartheid-era FM Pik Botha dies Botha's death provoked mixed reactions in South Africa, where many feel his time under Mandela did not excuse the years he spent fervently defending apartheid [File: Liu Heung Shing/The Associated Press]](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/imagecache/mbdxxlarge/mritems/Images/2018/10/12/55f85276cebf44f894da317576d6ad0f_18.jpg)

Former South African Foreign Minister Roelof “Pik” Botha, a key figure in the country’s transition from the apartheid era to democracy, has died at the age of 86.

Botha’s son confirmed to local media on Friday that his father died in his sleep after succumbing to an illness.

Botha served as foreign minister for 17 years until the end of apartheid in 1994, then joined Mandela’s cabinet after the end of white-minority rule and the country’s first non-racial election in 1994.

Botha was part of successive governments who kept Mandela in jail.

Although he was regarded as a liberal figure within apartheid-era politics, he spent most of his career defending the oppressive system.

Botha was often called on to justify the continued imprisonment of Nelson Mandela and other political opponents, however, he told Al Jazeera in 2013 that, privately, he had long lobbied for Mandela’s release, which eventually came in 1990.

“I remember in 1982, I submitted a memorandum to the cabinet, prepared by my department, to the effect that Nelson Mandela ought to be released, that we are making a bigger martyr of him every day he stays in prison and that his international acclaim and status would be growing to an extent where we would not be able to handle it any longer. Unfortunately, at that time, it was shot down,” he said.

“Here you had someone who spent 27 years in prison, the day he was released he displayed the attitude and acumen of a person who has been a president before. Amazing, amazing, what insight he had into the minds of people and, for that matter, into world affairs,” Botha told Al Jazeera at the time.

Famously described by one Western diplomat as a “good man working for a bad government”, Botha was committed to establishing a stable post-apartheid South Africa.

“We handed over power but we were not capitulating. You do not capitulate and surrender when you do the right thing. You liberate yourself, that’s what we did. It was not a capitulation, it was liberation,” he said.

|

| Botha (centre, standing) was minister of mineral energy affairs under Mandela [File: Lynne Sladky/The Associated Press] |

From apartheid to the ANC

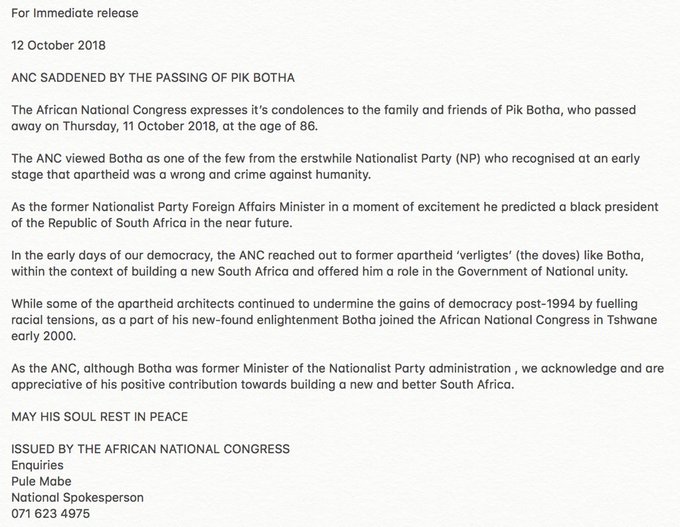

Botha’s death provoked mixed reactions in South Africa, where many feel his time under Mandela does not excuse the years he spent fervently defending apartheid.

The ruling African National Congress (ANC), which Botha joined in 2000, issued a statement on Friday, saying its members were “saddened” by news of his death.

“The ANC viewed Botha as one of the few from the erstwhile National Party (NP) who recognised at an early stage that apartheid was a wrong and a crime against humanity … although Botha was a former Minister of the Nationalist Party administration, we acknowledge and are appreciative of his positive contribution towards building a new and better South Africa,” the statement read

Derek Hanekom, the country’s tourism minister, praised Botha’s intellect in a statement on Twitter.

“I spent two years sitting next to him in the first cabinet of our new democracy, under President Nelson Mandela. I wish I kept all the scribbled notes he passed on to me. Great intellect, great sense of humour! Condolences to the family,” Hanekom said.

For others, however, Botha’s passing was a cause for celebration, with one Twitter user asking where celebratory drinks would be held and many questioning whether Botha would be given a state funeral.

Born in Rustenburg, a city in Transvaal province, in 1932, Botha embarked on a diplomatic career in the early 1950s with a posting to the South African mission in Stockholm.

Botha rose to the roles of envoy to the United States and United Nations, before shifting his focus to politics in the 1970s.

In 1977, he became South Africa’s foreign minister under PW Botha, to whom he was not related.

During his career, he had several clashes with PW Botha’s hardline government, including in 1984 when his comment that a black president could one day rule the country was met with a public rebuke from his boss.

Botha was then forced to issue a letter stating that a black president was not consistent with government policy.

Botha served for two years as minister of mineral energy affairs under Mandela until 1996, when he retired from politics.

He is survived by his wife Ina and their four children.