The House of Representatives on Tuesday okayed President Muhammadu Buhari’s plan to borrow additional $22.79bn from external sources for the funding of Federal Government infrastructural projects.

The loans are part of the 2016–2018 Federal Government External Borrowing (Rolling) Plan laid before the House on March 5, 2020, before the President’s fresh loan request of $5.5 billion on May 28, 2020.

The Senate had approved the loan on March 6 but the House suspended its consideration of the request indefinitely.

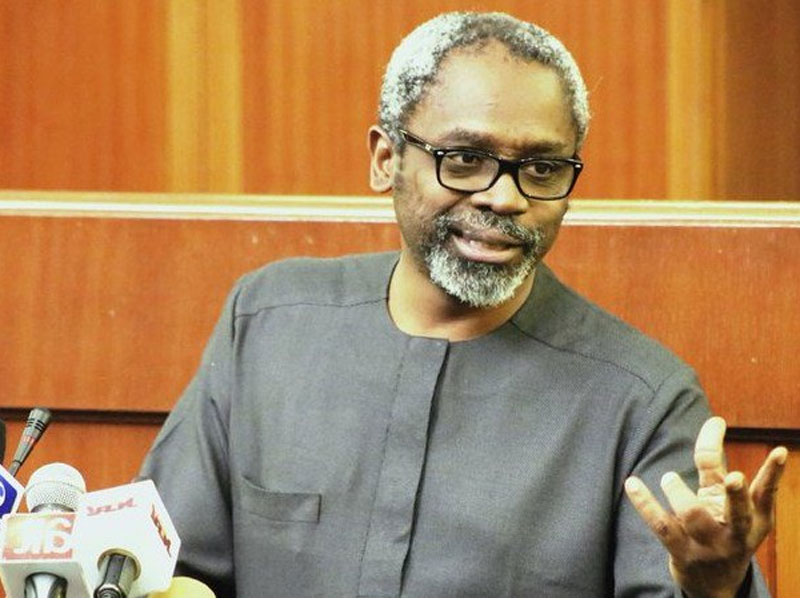

Almost two months later, Speaker of the House, Femi Gbajabiamila, on Tuesday explained why the lawmakers suspended the consideration of the loan request.

While presiding over Tuesday’s plenary, Gbajabiamila stated that the suspension was due to the protest by National Assembly members from the South-East over the exclusion of the geopolitical zone.

Chairman of the Committee on Loans and Debt Management, Ahmed Safana, presenting his report, notified the lawmakers that the Port Harcourt-Maiduguri rail line project had been inserted into the borrowing plan.

In its recommendation, the committee asked the Federal Government to source funding for the Port Harcourt-Maiduguri rail line in the next borrowing plan.

Below is the breakdown of the loans.

• World Bank – 2, 854, 000, 000

• African Development Bank – 1,888, 950, 000

• Islamic Development Bank – 110,000,000

• JICA – 200,000,000

• German Development Bank – 200,000,000

• China Eximbank – 17,065, 496,773

• AFD – 480,000,000

Total = 22, 798, 446, 773

According to Wikipedia, available data shows Nigeria’s external debt levels of $27 billion is now about 75% of external reserves of $35 billion. This is the highest we have seen since 2005. An inverse of the data means Nigeria’s external reserves can now only cover 133% of its external debts and 23x its debt service.

In a Forbes report, Paris-based sovereign debt expert Andrew Roche has pointed out that while the country’s debt as a proportion to GDP is a reasonable 20 percent, debt servicing costs make up fully two-thirds of retained government revenue, a startlingly high figure and a datum its government goes some lengths to de-emphasize.

Without an honest and frank government acceptance of the situation, Nigeria’s chances of escaping its self-inflicted debt trap are vanishingly small.

Another problem facing the country is that while most developing countries take advantage of concessionary financing from the World Bank or other international institutions, Nigeria’s debt profile is now increasingly made up of commercial debt. Its recent Eurobond issuances in London, for example, came at a relatively high yield, which makes its economy especially vulnerable to external shocks, such as a sustained drop in oil prices.