Nigeria became a top drawer when she joined the league of crude oil exporters in 1958. With that achievement, Shell d’Arcy, the company that first struck oil, took significant move to construct the first Port Harcourt refinery in 1965. After that quantum leap why has none of the International Oil Companies (IOCs) otherwise known as super majors including Shell got involved in constructing any other refinery in Nigeria? To unravel what went wrong on issues of petroleum refining, importation, subsidy and the attendant inefficiencies, we should not pass over the IOCs long absence in this aspect of the Nigerian downstream petroleum sector. GLOBAL PETROLEUM POLITICS.

In finding explanation on how to refine locally, we should be guided by this axiom; that the best answers are found in asking the best questions. Why are the super majors not investing in the Nigerian downstream sector even when they do so in non-oil producing consumer nations? The petroleum industry is divided into two main categories videlicet the National Oil Companies (NOCs) and the International Oil Companies. It is also segmented into upstream, downstream, pipeline, marine, as well as service and supply. The Upstream is the searching for potential underground and underwater oil and gas fields, drilling of wells and recovering crude oil and, or natural gas to the surface. The downstream sector is made up of the processing plants called refineries and sometimes petrochemical plants, distribution and marketing of byproducts.

Our discourse here is the absence of super majors in the downstream especially as it relates to refining. National Oil Companies and Super Majors National Oil Companies: They are petroleum companies nationally owned and operated by governments. More than half of the world’s reserves are controlled by NOCs. Most global oil supplies are from the National Oil Companies. The development of NOCs in countries with large oil reserves was a struggle to control petroleum resources. The top 10 NOCs in the world are: Saudi Aramco (Saudi Arabia), National Iranian Oil Company (Iran), Qatar Petroleum (Qatar), Iraq National Oil Company (Iraq), Petroleos de Venezuela (Venezuela), Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (UAE), Kuwait Petroleum Corporation (Kuwait), Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (Nigeria), Libya National Oil Corporation (Libya), and Sonatrach (Algeria). (Courtesy: Petroleum UK). These NOCs belong to OPEC. There are also NOCs that are non – OPEC. International Oil Companies: They are publicly owned petroleum companies not operated by governments. The six largest publicly traded IOCs in the world a.k.a. super majors are ExxonMobil (Texas, USA), Royal Dutch Shell (The Hague, Netherlands), BP/Amoco (London, UK) Total SA (Paris, France), Chevron (California, USA) and ConocoPhillips (Texas, USA). Market and Price Control We should underscore the point that a cold war between the NOCs and the IOCs existed over time. While NOCs control the reserve size of the industry, IOCs tend to control both reserve size and the market using technology and expertise to manipulate and dominate. NOCs control about 88 percent of the oil reserves while the IOCs control only 6 percent of the reserves. It should however be noted that NOCs perceived control of the reserve size does not translate to large revenues. International Oil companies control the price of oil paid to petroleum producing nations.

It was in response to imbalances in the bargaining power of IOCs that OPEC was founded in 1960. OPEC encouraged its members to put more pressure on Oil Companies to offer more concessions and also for NOCs to devise better means of extracting and refining with a view to reduce reliance on IOCs. Super Majors Subsidy Many governments do not operate nationally owned oil companies. These governments grant publicly owned petroleum companies subsidies. The reason is that oil is of strategic importance to a nation’s security. These subsidies are also granted by governments not to drive companies overseas. The fear is that home countries will become even more dependent than they already are on foreign nations for oil. So for those governments their oil companies are protected via subsidies at home. The United States government for instance provides large subsidies to publicly owned oil companies a tax rate of nine percent, well below the standard 25 percent corporate rate.

NIGERIA AND THE SUPER MAJORS

Shell struck oil at Oloibiri in present day Bayelsa State on Sunday 15th January 1956 after about half a century of petroleum prospecting in the Niger Delta. The company extracted and exported crude and refined abroad. In 1965, Shell constructed the 38,000 barrels per day capacity refinery in Port Harcourt. It was expanded to 60,000 barrels per day after the Nigerian civil war. Nationalisation of Downstream Assets and Consequences In 1971, Nigeria was to join the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). A requirement was that a country must have a 51 percent stake in the industry.

The then military government of General Yakubu Gowon promulgated the indigenization decree to increase the participation of Nigerians in businesses dominated by foreigners. With that law by fiat, the Nigerian National Oil Corporation (NNOC) was formed as the National Oil Company. The Shell Refinery was then nationalized. One is not sure whether there was a buy out of the nationalised Shell refinery. That was an albatross around Nigeria’s neck and dimmed the spirit of international oil companies to further invest in refineries. Before indigenization the Federal Government had limited involvement in the oil industry; just taxes and royalties were paid by the oil companies.

Nationalisation may have generated large amounts of income and technology for Nigeria but the country paid dearly for it. The Nigerian state built three more refineries in Warri (1978), Kaduna (1980) and the 2nd Port Harcourt (1989). The Eleme Petrochemical Complex (1990) now privatised completes the list. By 1979, the government of then General Olusegun Obasanjo merged the NNOC and the Ministry of Petroleum Resources to form what is now the NNPC to gain more power over the allocation and concessions through the NNOC. The NNPC then acquired about 60 percent participation in the oil industry; a regime that is still operational today. Again, the Obasanjo administration in 1978 nationalized Shell and BP downstream facilities because their home government support for the defunct apartheid regime in South Africa. Shell was changed to National and BP became AP. That again may have put the death knell on IOCs downstream investments in Nigeria. Expertise to explore and develop crude makes IOCs almost indispensable in Nigeria. If not how do we explain their heavy investment in the downstream sector in countries that are net oil importers, and worse still in non-oil producing consumer nations. Exxon Mobil Corporation of the United States, the largest refiner in the world has no refinery in Nigeria. It owns the ExxonMobil Refining & Supply Company in Singapore with a refining capacity of 605,000 barrels per day capacity. That refinery is the 5th largest in the world. Its refining capacity is higher than our four refineries combined capacity of 445,000 barrels per day. Also, Shell the biggest player in Nigeria, owns the Shell Eastern Petroleum (Pte) Ltd Singapore with a refining capacity of 462,000 barrels per day. It is the 13th largest in global ranking (Courtesy: OGJ). POSSIBLE SOLUTIONS With the legal and regulatory frameworks of decrees, corporate entities could not enforce their rights.

It became expedient for international oil companies to operate only in the upstream sector as it is today. Petroleum Industry Bill: The bill to provide for the establishment of legal, fiscal and regulatory framework for the Petroleum industry in Nigeria and other related matters otherwise known as the Petroleum Industry Bill (PIB) is a way to go. That bill proposed the establishment of a progressive fiscal framework that encourages further investment in the industry while optimizing revenues accruing to government. The bill also proposed a Downstream Petroleum Regulatory Agency. It makes the Agency a body corporate with perpetual succession. It means the Agency can sue and be sued. CONCLUSION One believes that Nigeria’s nationalisation even when it increased the revenue base to the nation caused a problem in that the International oil companies were forced out of the downstream sector. As a solution, we may renegotiate with these oil companies as they have the technology and expertise to dominate the upstream and downstream sectors for now. We may also tinker and reform our fiscal, legal and regulatory frameworks to accommodate the partnerships we longingly desire with IOCs in the construction of refineries.

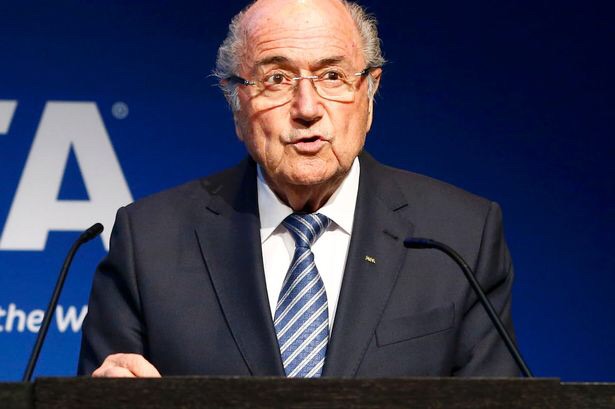

Sonny Atumah is a member of the Middle East Petroleum