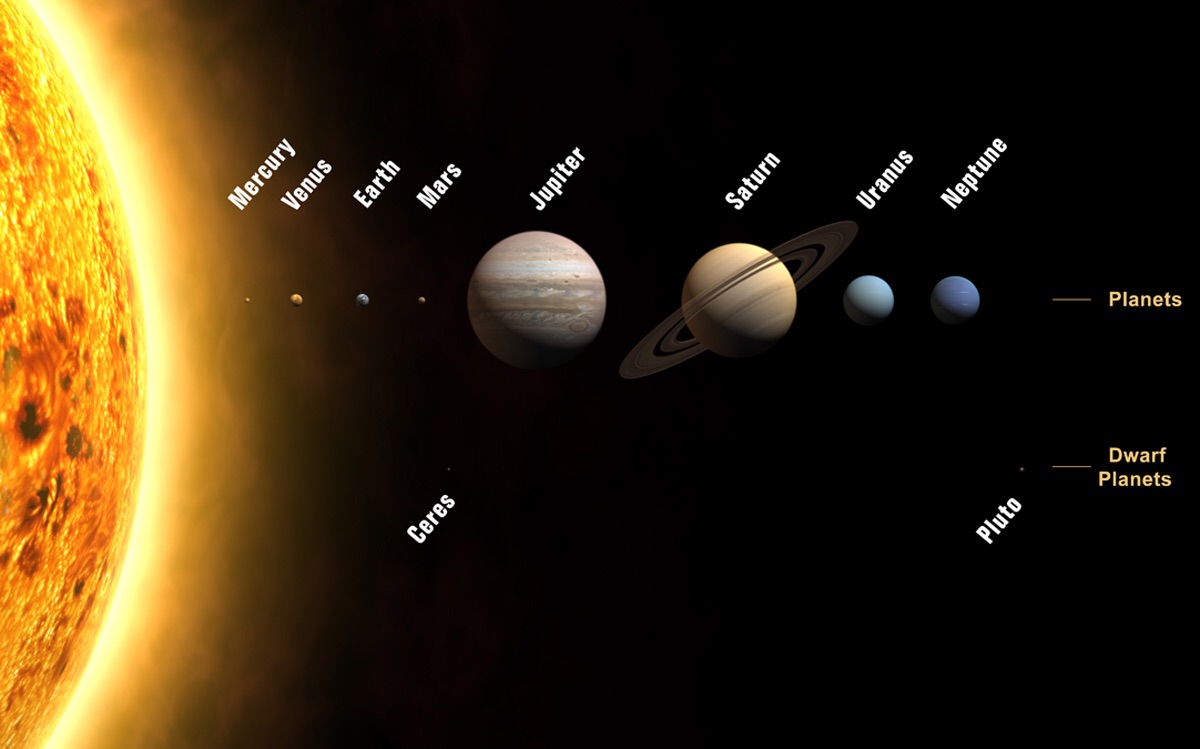

Remarkable new images from NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft are drastically rewriting scientists’ understanding of Pluto and its large moon Charon and bolstering the case for the exploration of a host of other small worlds that lie at the shadowy edge of the solar system.

The images, beamed to Earth on Wednesday, are the first from the probe’s closest approach to Pluto and its moons. Their unveiling has captivated world attention and revealed the most distant planetary bodies ever explored in an entirely new light.

The images, beamed to Earth on Wednesday, are the first from the probe’s closest approach to Pluto and its moons. Their unveiling has captivated world attention and revealed the most distant planetary bodies ever explored in an entirely new light.

The New Horizons spacecraft has traveled more than nine years and over three billion miles.

“This system is amazing,” said principal investigator Alan Stern during a news briefing at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Md., where the mission is based.

Among the most important highlights from the mission is the revelation that Pluto has been active in the geologically recent past.

The closest image seen so far features towering mountains thought to be made of ice. A striking absence of craters suggests the dramatic terrain can be no more than 100 million years old.

The astonishing implication is that when dinosaurs were walking on Earth, parts of Pluto’s surface were being reshaped by subterranean processes, powered by heat from an unknown source.

The evidence for a dynamic history on Pluto is a clear vindication for the New Horizons mission, which some experts thought would reveal little but a geologically inert relic largely unchanged since the solar system’s deep past.

It also suggests that other large bodies in the Kuiper belt may be similarly worth exploring with dedicated missions of their own.

“We’ve settled the fact that these very small planets can be very active after a long time,” Dr. Stern said.

Equally surprising is Charon, Pluto’s large moon, which has turned out to have an improbably diverse surface including an enormous system of troughs and cliffs that extends for 1,000 kilometres. A patch of dark material at Charon’s north pole, which the science team has informally dubbed “Mordor,” looks to be a thin veneer, supporting speculation that it may consist of material deposited from Pluto or elsewhere in the system.

“Charon just blew our socks off,” said deputy project scientist Cathy Olkin. “The whole team is abuzz.”

New Horizons passed within 12,500 kilometres of Pluto on Tuesday morning. Mission team members spent the day in nervous anticipation during a long period of radio silence when the probe was preoccupied with a tightly scheduled itinerary of science observations.

The mood turned to one of exuberance on Tuesday night when a signal from the spacecraft confirmed that it had survived the long-awaited flyby and that its science instruments had performed as planned.

Scientists got down to business early Wednesday morning when New Horizons began transmitting back a “waterfall of data,” said Dr. Stern.

Only a handful of images were released, with the promise of much more to come as the probe continues beaming back a massive cache of measurements and images.

One image offers the best look yet at Hydra, a smaller moon in the system. Although pixelated, it demonstrates that Hydra is a small, oblong body with a high surface reflectivity that matches the characteristics of ice.

Along with Pluto’s other moons, Hydra is thought to have formed out of the debris from a massive impact. Most of the material coalesced into Charon, a moon that is near enough in size to Pluto that the two are sometimes called a double planet.

Earth and the moon are similarly paired and evidence suggests that the moon likewise was created when a planet-sized object collided with Earth early in the solar system’s history. Part of the scientific rationale for the New Horizons mission is to learn what the system might reveal about the origins of the Earth-moon system.

New Horizons is now rapidly moving away from Pluto. It will complete its encounter with a search for any rings of dust and debris that might encircle Pluto and that would likely be easier to spot when backlit by the sun.

Meanwhile, the mission team is openly lobbying NASA for an extended mission that would allow New Horizons to visit a Kuiper Belt object on its way out of the solar system.

New Horizons has enough propellant left to adjust its trajectory and enable such an encounter as long as the adjustment is made by late October.

Heidi Hammel, executive vice president of the U.S. Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy said New Horizons’ success was whetting appetites for follow-on missions to distant planetary targets.

“There’s sort of an underground sentiment that we need to get back to the outer solar system,” she said, adding that new technologies were being identified that would enable such missions to proceed in less time and at lower cost.

“New Horizons has set the standard for that,” she said.

The Globe and Mail