verybody agrees that Republicans will win the midterm elections and stand a better-than-ever chance of controlling the Senate. For months, a debate has raged over why. One analysis is structural. Democrats rely heavily on minorities and the young, who tend to skip midterm elections, making the electorate more Republican than the one that shows up at the polls every four years. Additionally, the Senate races this year force Democrats to defend far more seats, many of which are held in Republican territory.

The competing analysis is that the election represents a “wave.” Wave-theory advocates don’t deny that structural forces favor the GOP, but they tend to emphasize a backlash by the voters against President Obama and his policies. This way of thinking has particular appeal to conservatives, like Michael Barone (“That should settle the ongoing argument in psephological circles about whether this is a “wave” year”), Jennifer Rubin (“The intensely anti-Obama wave will lift many, but not all, Republican boats”), and Josh Kraushaar. Wave advocates see the midterms as America’s righteous punishment against liberal overreach.

Related Stories

Scientists Also Lying About Ebola, Explains George F. Will

Republicans Trying to Woo, or at Least Suppress, Minority Vote

Republican Joni Ernst Admits Why Republicans Really Hate Obamacare

It is certainly true that Obama has poor approval ratings. (One does not need an election to measure indirectly what polling can show directly.) But this, in turn, returns us to the original question of locating the source of the voters’ displeasure. Are Americans unhappy with Obama’s policies, per se, or are they acting out a broader displeasure with the state of the economy, or American politics? To what extent should we think of the electorate as expressing conservative (or, at least, anti-liberal) impulses?

One way to test the two theories against each other is to consider governor’s races. The smaller, non-presidential electorate still favors Republicans, but the map does not. Senate seats turn over every six years, and six years ago a Democratic wave election helped the party capture lots of normally red territory, making this election especially challenging. Governorships, on the other hand, turn over every four years. And four years ago, Republicans carried off a rout. So in the governor’s races, it is Republicans now fighting in neutral or hostile territory.

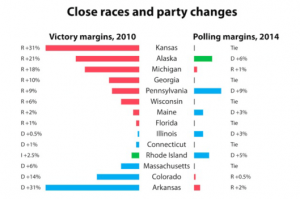

And as Sam Wang shows, governor’s races in many states have lurched decisively toward Democrats:

The huge turnabout in Arkansas represents the term-limited retirement of highly popular Democrat Mike Beebe. The blue lines at the top are a measure of the backlash against Republican governors, many of whom enacted policy agendas reflecting the national-level Republican vision and find themselves in danger of losing reelection.

Kansas, of course, offers the quintessential case of a state-level backlash. Governor Sam Brownback explicitly fashioned his state as a laboratory for the conservative program, especially on taxes, and the results have been catastrophic. (Josh Barro reports today that the state’s revenue loss, which Brownback explained away as temporary, runs even deeper than expected.) Wisconsin’s Scott Walker, Michigan’s Rick Snyder, and Florida governor Rick Scott, all circa-2010 Republican governors in purple states, all face dire threats of losing their seats after a single term. North Carolina GOP governor Pat McCrory, not facing reelection until 2016, has so poisoned the state’s voters against his party that Democratic Senator Kay Hagan leads nearly every poll.

Was it something I did? Photo: Mark Wilson/2010 Getty Images

North Carolina and Kansas are the two states where Democrats seem to be dramatically over-performing the fundamentals. (They have a chance to pull a surprise win in Georgia, but that would be attributable to the state’s rapid growth of Democratic voters.) North Carolina and Kansas have in common Republican governors who have enacted sweeping, controversial agendas that have turned their party’s Senate candidates into quasi-incumbents.

Conservatives have strained to argue that Obama’s agenda, and especially his hated health-care law, explain his party’s struggle. “Throughout this election cycle,” writes Kraushaar, “the Democrats have been dogged by the president’s health care law.” Karl Rove gloats, “the president’s health law may end up as a decisive cause of two epic midterm defeats for the Democratic Party.”

That certainly describes the kind of campaign Republicans have wanted to run, but not the one they actually have. Red-state Republicans Mitch McConnell and Tom Cotton have dissembled incoherently rather than endorse the anti-Obamacare absolutism favored by the conservative base. Scott declared himself in favor of accepting the law’s Medicaid expansion last year. This summer, doomed Pennsylvania Republican governor Tom Corbett finally gave in. North Carolina’s Thom Tillis, who once boasted — accurately — of having “stopped Obamacare’s Medicaid expansion cold,” announced this week that the state should “consider” accepting it.

In McConnell’s case, the Republican is bedeviled by a popular Democratic governor who has thrown himself fully behind implementing Obamacare, with impressive results. In many of the other states, the general pro-Republican thrust of the election is running up against a localized backlash against Republican policies. If Obama were the only incumbent, Republicans would have locked up the Senate majority by now and might be poised to enjoy a genuine wave. Unfortunately for them, they have had the chance to govern.