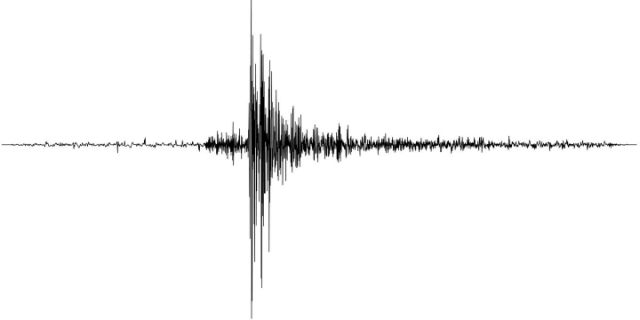

- Earth makes a tiny seismic rumble every 26 seconds.

- Is the pulsating caused by ocean waves, volcanoes, or something else completely? Theories abound.

- The “microseism” doesn’t seem to be hurting anything and has not been a high priority.

Why is Earth pulsating every 26 seconds, and why can’t scientists explain it after 60 years? This is an enigma wrapped in a periodically predictable mystery motion. It could be a harmonic phenomenon, a regular seismic chirp caused by the sun’s energy, or a beacon drawing scientists to its source to begin a treasure hunt.

In the early 1960s, a geologist named Jack Oliver first documented the pulse, also known as a “microseism,” according to Discover. Oliver, who worked at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Geological Observatory at the time, heard the noise, but didn’t have the advanced instruments seismologists have now at his disposal.

Since then, scientists have spent a lot of time listening to the pulse and even finding out where it comes from: “a part of the Gulf of Guinea called the Bight of Bonny,” Discover says.

Some researchers think the pulse has a kind of prosaic cause. Under the world’s oceans, the continental shelf acts as a gigantic wave break—it’s the boundary off the very far edge of, for example, the North American continental mass where the highest part of the plate finally falls off into the deep abyssal plain. Scientists have theorized that as waves hit this specific place on the continental shelf in the Gulf of Guinea, this regular pulse is produced.

If that sounds improbable, consider all the different shapes of drums, from timpani to bass drums to bongos that you hit with your hands. It’s not impossible that just one shape of continental shelf “drum” would create the right harmonic bang to rattle the Earth. If that’s true, we’re probably lucky it’s just one.

📚 The Best Earth Science Books

But other researchers think the cause is a volcano that’s also very near the critical spot: “That’s because the pulse’s origin point is suspiciously close to a volcano on the island of São Tomé in the Bight of Bonny,” Discover explains. And there’s a similar volcanic microseism that’s already well documented in Japan.

It seems like reams of new scientific research emerge every day, but the mystery pulse is a good reminder that so much remains to be discovered. Scientists have studied the pulse and debate its origin, but it just hasn’t reached a tipping point of interest to be solved. Discover explains that researchers have likely been studying higher-priority seismic events instead, which makes sense.

This year, for example, seismologists have an important opportunity to study a much quieter Earth during global quarantine. That could mean they all redouble efforts on high-priority subjects, or it could mean that the right listener at the right time could finally understand the 26-second chirp once and for all. In a perfect world, we could have both.