This article first appeared on The Conversation.

When the chief executive of Goldman Sachs, Lloyd Blankfein, told a newspaper the company was “doing God’s work,” his appeal on behalf of higher powers was an attempt to rescue the tainted reputation of not only his own investment bank but the entire industry.

Subscribe now – Free phone/tablet charger worth over $60But for the Catholic Church, even this most obvious of strategies might not be enough to stem an inexorable decline.

The church is one of the oldest and most profitable brands in history. Financial details are kept sketchy, but this vast multinational dwarfs any other.

The Economist has estimated that in 2010, spending by the U.S. branch of the church and its various entities (probably the wealthiest and least opaque of the global organization’s chapters) was $170 billion. Yet the church is beset by problems.

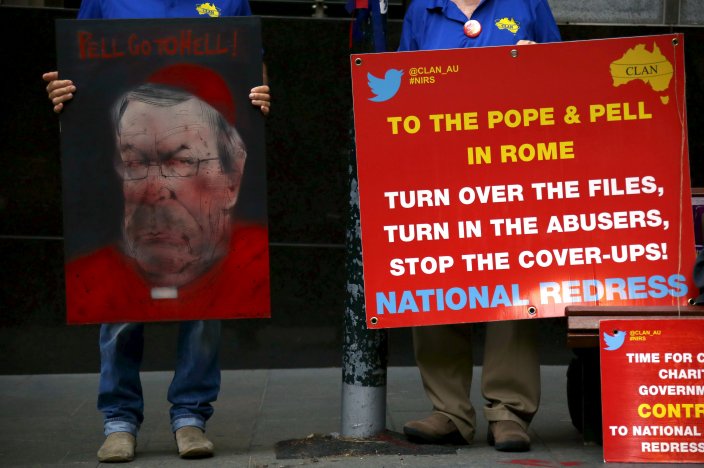

As many brands have found out (the BBC’s experience of sex abuse claims, for instance), handling the fallout from a disgrace is perhaps more important than the scandal itself. The drip feed of negative headlines associated with sexual abuse and its cover-up has irreparably tarnished the Catholic brand for many.![]()

There is a more fundamental threat to Catholicism, however: irrelevance.

It is testament to Pope Francis’s skill that he has managed to reinvigorate the church’s standing despite continuing corruption and abuse controversies. Perhaps in a different life his calling would have been working for a top advertising agency.

The church has refocused on its core brand strength of representing the vulnerable and regained moral momentum through its campaigns focusing on peace, poverty, migration and the environment. For example, the pope’s decision to take three refugee families back to the Vatican following his visit to the Greek island of Lesbos. Here the church has projected a clearer, stronger and more urgent message that resonates with many.

This stands in stark contrast to the sociocultural values espoused by the church. These are now in opposition to majority moral attitudes in many parts of the world.

Such tension may work in the short term for niche brands with a small group of loyal countercultural followers. Think Punk IPA beer or extremist violence fanatics—united by their love of beards but ignored by the mainstream. Standing for fringe values is obviously not viable for mass market appeal, however.

Mobile phone company Nokia disappeared because it failed to keep up with the changing expectations of consumers over the size of its phone screens. What, therefore, are the consequences of diverging from public opinions on and experiences of homosexuality, female equality, married life, sex and parenthood?

Perhaps we can see it in the stunning decline of Catholic congregations across large parts of Europe and in North and South America.

Comforting Distractions

A brand is two things. First, it is a solution to a customer need. Humans look for meaning in a chaotic universe, and religions compete with distilleries, retailers, social networks, movies and many other things to provide if not satisfying answers then at least comforting distractions.

The Catholic Church is no longer providing a solution that resonates for many. And fewer believe in such solutions when they are proposed by a discredited brand.

Secondly, a brand is a community. When that community stands in opposition to the values and identities of many of its members, it pushes them out. Their loss reduces diversity and damages the creativity and vibrancy that keep a brand alive and attractive. Those who remain are more exclusive and out of step with outsiders.

As people are pushed out or left to feel unwelcome, they look elsewhere. Gay clergy and members are forced to mask their identity if they are to remain. TheLGBT Catholic community monitors gay-friendly Catholic parishes. Many have split from the mainstream church, and the threat of a schism over homosexualitycontinually looms.

Nonbelief relentlessly expands its market share. Young people in America are significantly less religious than older generations.

Meanwhile, niche operators are moving in: syncretic religions that fuse Christianity with traditional or new age beliefs are expanding rapidly in Latin America. Non-Catholic Christian denominations are building megachurchesthroughout Africa.

These flexible competitors have aligned themselves closely with local customs, interests and landscapes to offer a more relevant and inclusive brand.

The problems faced by the Catholic Church are not unique. Religious brands of all stripes are facing similar existential crisis. From Mecca to Rome to India’sVaranasi, sociocultural changes are outpacing the ability of traditional religious brands to keep up, and they are failing to provide brand solutions and communities that appeal.

Trapped in a squeezed mid-market, they are caught between liberalization to the point of Episcopalian ephemera, whereby doctrine becomes so openly interpreted that a religion is no longer centrally organized or structurally cohesive. Alternatively, they survive by fueling the fires of a shrinking, and otherwise off-putting, conservative minority.

Disconnections

The marketing response has repeatedly been one of rage. From political Hindus suppressing dissent to the murder of blasphemous bloggers by Islamists, the evidence is that religious brands cannot and will not accept change.

This only serves to underline the disconnection between religious brands and social reality. Research suggests that anti-gay, anti-science attitudes are turning people away from religion in the U.S., for example. In a globalized and hyper-connected world, scandals, hypocrisy, lies, financial cover-ups and generally obfuscated moral messages are shared, picked apart and rejected faster than ever.

Instead, a reflective marketing approach is required. One that recognizes that individuals and societies are changing and that brands need to change as well if they are to survive. The Catholic Church needs to research, respect and respond to changing consumer needs and values. If it does not, it will continue to decline.

Religious brands answer to a higher power: the consumer. Even the world’s oldest, wealthiest and most powerful brands are not infallible.

Brendan Canavan is lecturer in marketing at Britain’s University of Huddersfield.