Boris Johnson’s appointment as the UK foreign secretary is raising eyebrows in Africa, writes Zimbabwean filmmaker and columnist Farai Sevenzo.

Since the UK’s EU referendum, political drama stranger than fiction has gripped observers all over the world – not just within Britain.

Unclear about what the Brexit vote would mean, Africans still took to the Twittersphere in grudging admiration of the smoothness of the transition of power, and wondered why David Cameron had not just rigged the referendum and awarded his point of view the customary 99.9% voter approval common in less ancient democracies on African lands.

In just three weeks from the vote, a new Prime Minister, Theresa May, took charge after the honourable departure of her predecessor and promised to be there for the less privileged, to understand the struggles of the working class and to get equal pay for women.

She said plainly that she gets that “if you’re black, you’re treated more harshly by the criminal justice system than if you’re white”.

Then she appointed Boris Johnson as her foreign secretary.

Image copyrightAFP

Image copyrightAFPThe former London mayor is a consummate politician, whose appetites are as varied as his wit and a favourite of the press for the colourful copy his life and personality consistently deliver.

But there is the whiff of a 1940s colonial district administrator about his utterances when it comes to people and cultures from beyond his social circles.

Born in 1964, his attitude is from an earlier century, full of the arrogance of Empire and the condescension of so-called “civilisers”.

This is Mr Johnson in 2002 writing a column critical of then Prime Minister Tony Blair’s trips abroad:

“It is said that the Queen has come to love the Commonwealth, partly because it supplies her with regular cheering crowds of flag-waving piccaninnies…

“They say he is shortly off to the Congo. No doubt the AK47s will fall silent, and the pangas will stop their hacking of human flesh, and the tribal warriors will all break out in watermelon smiles…”

Mr Johnson has since apologised for these words, but they remain etched in history as at worst a bully’s insult to those cheering children and at best the kind of joke delivered to like-minded people in the Monday Club or at an apartheid golf course.

During the referendum debate, Mr Johnson suggested that US President Barack Obama, who supported the UK remaining in Europe, had removed a bust of Winston Churchill from the Oval office because of an intrinsic dislike of icons of empire.

“Some said it was a snub to Britain,” he wrote. “Some said it was a symbol of the part-Kenyan president’s ancestral dislike of the British Empire – of which Churchill had been such a fervent defender.”

Both Britain’s World War II leader and Mr Obama had American mothers – but it is the “part-Kenyan” difference Mr Johnson sought to highlight, rather than the glaring similarities of the men he was writing about.

Image copyrightAFP/GETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightAFP/GETTY IMAGESIn February 2015, Mr Johnson aimed his acid pen at Zimbabwe’s President Robert Mugabe on the occasion of his 91st birthday celebrations:

“In scenes reminiscent of the more disgusting and luxurious behaviour of the emperor Commodus, he will cause various exotic beasts to be slaughtered for the feast,” he wrote.

“A local farmer has procured two elephants, and after these rare and majestic creatures have been butchered for the delectation of the semi-deified Mugabe, there will be one more type of meat to come – an animal that you might think was semi-sacred, whose killing should be taboo, a creature that people would never normally dream of eating.

“Yes, a lion, the king of the animal kingdom, will lay down its life before the meat-maddened mob…”

Image copyrightEPA

Image copyrightEPAReaders of colonial classics may be transported to Conrad and his Heart of Darkness best, but the language is derisory and mocking here, the word “savages” hovering dangerously on the tip of his pen if not his tongue.

In the piece, he went on to bemoan former Prime Minister Tony Blair’s abandonment of white farmers in the former British colony: “Here we had people with close relatives in our own country – yes, our own kith and kin who had fought for this country in two wars and we did absolutely nothing.”

The reader was left in no doubt where his real sympathies lay in the story of that broken country, for black Africans too had died in great numbers for his country in two world wars.

There is passion in the new foreign minister’s words but accuracy, diplomacy and empathy are in short supply.

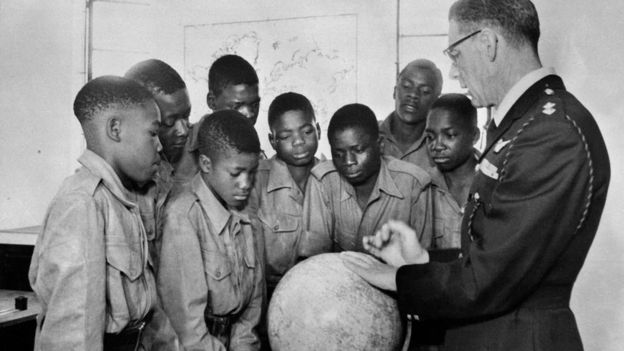

Image copyrightFOX PHOTOS

Image copyrightFOX PHOTOS Image copyrightREUTERS

Image copyrightREUTERSHe needs to up his diplomatic game despite his full Brexit in-tray – no part of modern Africa will stand much of what are essentially obnoxious out-of-date views of a continent many see as a rising market, whose citizens are well-read and tech-savvy and whose writers, black and white, have won five Nobel prizes for literature.

African citizens should be under no illusions though – the Cameron administration had already axed the office of minister for Africa, outsourced development budgets to the Department for International Development and cut the number of “cultural exchanges” between the UK and the African continent.

The new International Development Minister, Priti Patel, was cynical about the department’s existence and once openly campaigned for its abolition or metamorphosis into a trade body.

Diplomacy 101

The UK’s grip on her former colonies in Africa is loosening by the year – ask the Chinese.

There are genuine problems Mr Johnson must address on the African continent, from terrorism in North Africa to new trade deals to imploding political crises in South Sudan and Libya.

The finance minister of Zimbabwe has been pleading for a normalisation of relations with the UK after years of entrenched hostility, as a disgruntled population begins to find its voice of resistance.

At a time when the Ugandan army is entering South Sudan to evacuate people caught up in the fighting, African events will not wait for Mr Johnson to finalise Brexit.

Many Africans will be hoping the Foreign Office has a diplomacy 101 class suitable for the new minister, which, if anything, can remove the foot from his mouth.

Farai Sevenzo

Image copyrightFARAI SEVENZO

Image copyrightFARAI SEVENZO“No part of modern Africa will stand much of what are essentially obnoxious out-of-date views of a continent many see as a rising market, whose citizens are well-read and tech-savvy and whose writers, black and white, have won five Nobel prizes for literature.”

Source: BBC