RISING STAR: The Making of Barack Obama

By David J. Garrow.

William Morrow. 1,460 pp. $45.

Of the books that journalists and historians have written on the life of Barack Obama, three stand out so far. In “Barack Obama: The Story,” David Maraniss shows us who Obama is. In “Reading Obama,” James T. Kloppenberg explains how Obama thinks. In “The Bridge,” David Remnick tells us what Obama means.

Now, in a probing new biography, “Rising Star,” David J. Garrow attempts to do all that, but also something more: He tells us how Obama lived, and explores the calculations he made in the decades leading up to his winning the presidency. Garrow portrays Obama as a man who ruthlessly compartmentalized his existence; who believed early on that he was fated for greatness; and who made emotional sacrifices in the pursuit of a goal that must have seemed unlikely to everyone but him. Every step — whether his foray into community organizing, Harvard Law School, even the choice of whom to love — was not just about living a life but about fulfilling a destiny.

It is in the personal realm that Garrow’s account is particularly revealing. He shares for the first time the story of a woman Obama lived with and loved in Chicago, in the years before he met Michelle, and whom he asked to marry him. Sheila Miyoshi Jager, now a professor at Oberlin College, is a recurring presence in “Rising Star,” and her pained, drawn-out relationship with Obama informs both his will to rise in politics and the trade-offs he deems necessary to do so. Garrow, who received a Pulitzer Prize for his biography of Martin Luther King Jr., concludes this massive new work with a damning verdict on Obama’s determination: “While the crucible of self-creation had produced an ironclad will, the vessel was hollow at its core.”

***

By now the broad contours of the Obama story are well known, not least because Obama has repeated them so often. With Kansas and Kenya in his veins, he carries Indonesia in his memory, Hawaii in his smile, Harvard in his brain and, most of all, Chicago in his soul. “It wasn’t until I moved to Chicago and became a community organizer that I think I really grew into myself in terms of my identity,” he said in an interview about “Dreams From My Father,” his 1995 memoir. “I connected in a very direct way with the African American community in Chicago” and was able to “walk away with a sense of self-understanding and empowerment.”

Note how it was as much about Obama himself as any success he had in his organizing work. Inspired by Harold Washington, the city’s first black mayor, Obama began to discuss his political ambitions with a few colleagues and friends during his early time in the city. He wanted to be mayor of Chicago. Or a U.S. senator. Or governor of Illinois. Or perhaps he would enter the ministry. Or, as he confided to very few, such as Jager, he would become president of the United States. Lofty stuff for a 20-something community organizer who struggled to write fiction on the side.

Jager, who in “Dreams From My Father” was virtually written out, compressed into a single character along with two prior Obama girlfriends, may have evoked something of Obama’s distant mother, Stanley Ann Dunham. Like Dunham, Jager studied anthropology, and while Dunham focused on Indonesia, Jager developed a deep expertise in the Korean Peninsula. Jager was of Dutch and Japanese ancestry, fitting the multicultural world Obama was only starting to leave behind. They were a natural fit. Jager soon came to realize, she told Garrow, that Obama had “a deep-seated need to be loved and admired.”

She describes their life together as an isolating experience, “an island unto ourselves” in which Obama would “compartmentalize his work and home life.” She did not meet Jeremiah Wright, the pastor with a growing influence on Obama, and they rarely saw his professional colleagues socially. The friends they saw were often graduate students at the University of Chicago, where Sheila was pursuing her doctorate. They traveled together to meet her family as well as his. Soon they began speaking of marriage.

“In the winter of ‘86, when we visited my parents, he asked me to marry him,” she told Garrow. Her parents were opposed, less for any racial reasons (Barack came across to them like “a white, middle-class kid,” a close family friend said) than for concern about Obama’s professional prospects, and because her mother thought Sheila, two years Obama’s junior, was too young. “Not yet,” Sheila told Barack. But they stayed together.

In early 1987, when Obama was 25, she sensed a change. “He became. . . so very ambitious” very suddenly,” she told Garrow. “I remember very clearly when this transformation happened, and I remember very specifically that by 1987, about a year into our relationship, he already had his sights on becoming president.”

The sense of destiny is not unusual among those who become president. (See Clinton, Bill.) But it created complications. Obama believed that he had a “calling,” Garrow writes, and in his case it was “coupled with a heightened awareness that to pursue it he had to fully identify as African American.”

[The ‘racial procrastination’ of Barack Obama]

Maraniss’s 2012 biography deftly describes Obama’s conscious evolution from a multicultural, internationalist self-perception toward a distinctly African American one, and Garrow puts this transition into an explicitly political context. For black politicians in Chicago, he writes, a non-African-American spouse could be a liability. He cites the example of Richard H. Newhouse Jr., a legendary African American state senator in Illinois, who was married to a white woman and endured whispers that he “talks black but sleeps white.” And Carol Moseley Braun, who during the 1990s served Illinois as the first female African American U.S. senator and whose ex-husband was white, admitted that “an interracial marriage really restricts your political options.”

Discussions of race and politics suddenly overwhelmed Sheila and Barack’s relationship. “The marriage discussions dragged on and on,” but now they were clouded by Obama’s “torment over this central issue of his life . . . race and identity,” Sheila recalls. The “resolution of his black identity was directly linked to his decision to pursue a political career,” she said.

In Garrow’s telling, Obama made emotional judgments on political grounds. A close mutual friend of the couple recalls Obama explaining that “the lines are very clearly drawn. . . . If I am going out with a white woman, I have no standing here.” And friends remember an awkward gathering at a summer house, where Obama and Jager engaged in a loud, messy fight on the subject for an entire afternoon. (“That’s wrong! That’s wrong! That’s not a reason,” they heard Sheila yell from their guest room, their arguments punctuated by bouts of makeup sex.) Obama cared for her, Garrow writes, “yet he felt trapped between the woman he loved and the destiny he knew was his.”

Just days before he would depart for Harvard Law School — and when the relationship was already coming apart — Obama asked her to come with him and get married, “mostly, I think, out of a sense of desperation over our eventual parting and not in any real faith in our future,” Sheila explained to Garrow. At the time, she was heading to Seoul for dissertation research, and she resented his assumption she would automatically postpone her career for his. More arguments ensued, and each went their way, although not for good.

***

At Harvard, the Obama the world has come to know took clearer form. In his late 20s now and slightly older than most classmates, he had a compulsion to orate in class and summarize other people’s arguments for them. “In law school the only thing I would have voted for Obama to do would have been to shut up,” one student told Garrow. Classmates created a Obamanometer, ranking “how pretentious someone’s remarks are in class.”

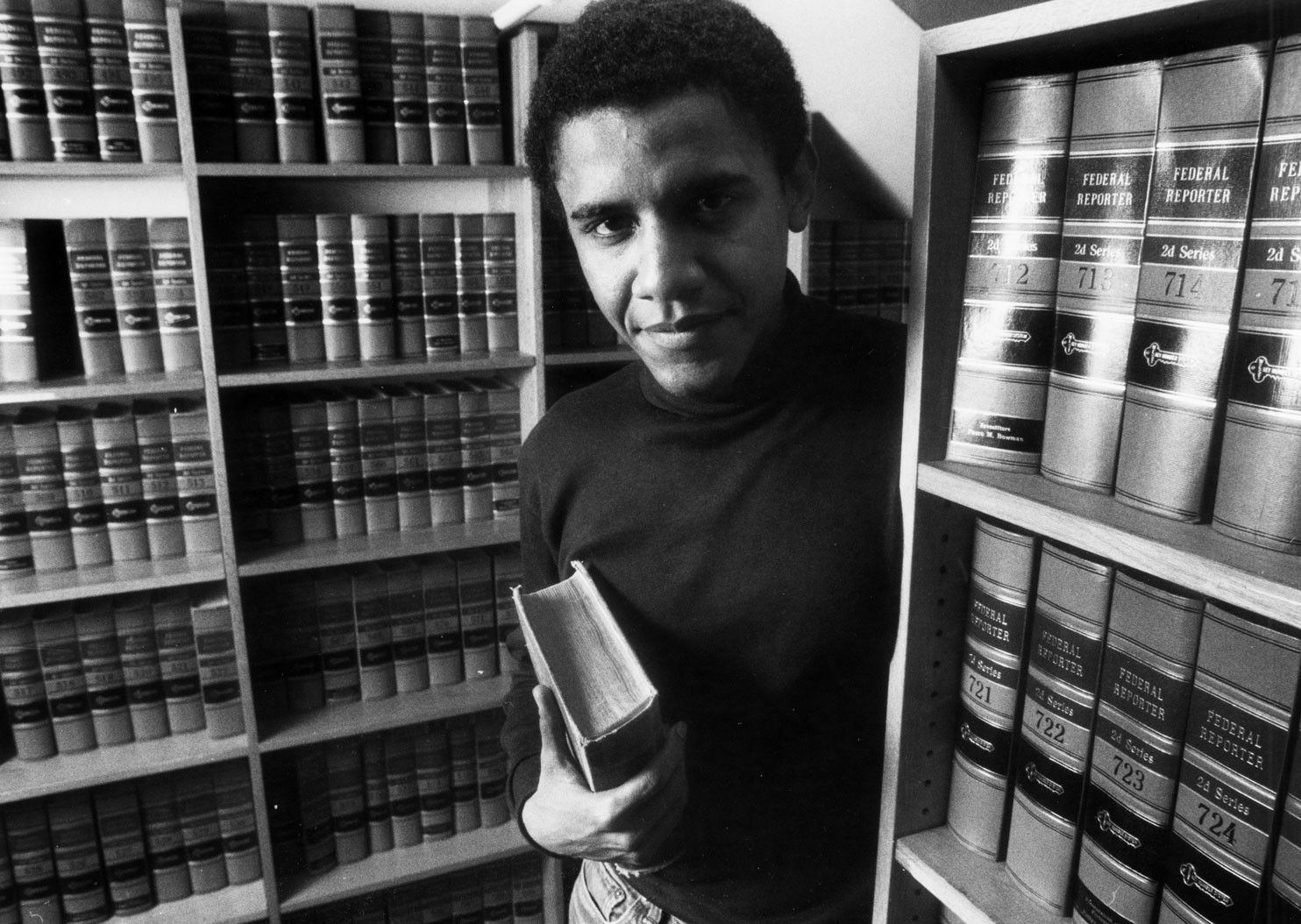

Such complaints aside, he was generally admired, including by his professors, one of whom wrote a final exam question around comments Obama had made in class. And his elevation to the presidency of the Harvard Law Review, the first time for an African American, signaled the respect the school’s elite students had for him — even if some liberal classmates later regretted their choice, finding Obama too conciliatory toward conservatives in their midst. Garrow re-creates the drama around the election, with Law Review colleagues debating the candidates’ legal acumen and leadership skills, as well as the possible history-making aspect of the selection. It is an unexpectedly riveting part of the book. The black editors on the staff began “crying and running and hugging” when the final choice was made — and with the national news coverage that followed, Obama’s star was on the rise.

Law school also provided Obama one of his most important intellectual interlocutors: classmate and economist Rob Fisher. They took multiple classes together and co-wrote a never-published book on public policy, titled “Transformative Politics” or “Promises of Democracy: Hopeful Critiques of American Ideology.” The manuscript explored the political failures of the left and right and expounded on markets, race and democratic dialogue, showing glimmers of the political philosophy and rhetoric that Obama would come to embrace. A few years later, Fisher helped Obama rethink “Dreams From My Father” (originally titled “Journeys in Black and White”), making it less a policy book and more a personal one.

Obama had met Michelle Robinson at the Chicago law firm where she worked — and where he was a summer associate — after his first year of law school, and the couple quickly became serious. However, Jager, who soon arrived at Harvard on a teaching fellowship, was not entirely out of his life.

“Barack and Sheila had continued to see each other irregularly throughout the 1990-91 academic year, notwithstanding the deepening of Barack’s relationship with Michelle Robinson,” Garrow writes. (“I always felt bad about it,” Sheila told the author more than two decades later. Once Barack and Michelle were married, his personal ties to Sheila was reduced to the occasional letter (such as after the 9/11 attacks) and phone call (when he reached out to ask whether a biographer had contacted her).

If Garrow is indeed correct in concluding that Obama’s romantic choices were influenced by his political ambitions, it is no small irony that Michelle Obama became one of those most skeptical about Obama’s political prospects, and most dubious about his will to rise. She constantly discourages his efforts toward elective office and resents the time he spends away from her and their two young daughters. Obama vented to a friend how often Michelle would talk about money. “Why don’t you go out and get a good job? You’re a lawyer — you can make all the money we need,” she would tell him, as the couple struggled with student loans and the demands of family and political life. (Garrow sides with Michelle, highlighting how, on the day after Sasha was born, Barack went downtown for a meeting.)

As he considered a U.S. Senate bid, Obama’s team commissioned a poll that covered, among other questions, his name. “Barry,” as he was known from childhood into his early college years, polled better than “Barack,” but Obama never considered resurrecting the old name. He had made his choice, of identity and image, long ago. Sheila recalls that one of the few times Obama became genuinely angry with her was in Hawaii, when she heard relatives calling him Barry, and she did so as well, just for fun. He became “irrationally furious,” she said. “He told me that under no circumstances was I ever to use that name with him.”

There was no going back.

***

“Rising Star” is exhaustive, but only occasionally exhausting. Garrow zooms his lens out far, for instance when he recounts the evisceration of Chicago’s steel industry in the early 1980s, providing useful context for Obama’s subsequent work. And he goes deliciously small-bore, too, delving into the culture of the Illinois statehouse, where poker was intense and infidelity was rampant. “There’s a lot of people who f—ed in Springfield,” a female lobbyist tells Garrow. “What else is there to do?” Obama, however, did not. “Michelle would kick my butt,” he told a colleague there. At times Garrow delivers information simply because he has it; I did not need a detailed readout of all of Obama’s course evaluations from his years teaching at the University of Chicago’s law school. (Turns out his students liked him.)

The book’s title seems chosen with a sense of irony. Garrow shows how media organizations invariably described Obama as a “rising star,” in almost self-fulfilling fashion. Yet, after nine years of research and reporting, Garrow does not appear too impressed by his subject, even if he recognizes Obama’s historical importance.

The author is harsh but persuasive in his reading of “Dreams From My Father,” for instance, calling it not a memoir but a work of “historical fiction,” one in which the “most important composite character was the narrator himself.” (Reviewers were impressed by it, but few who knew Obama well seemed to recognize the man in its pages.) He points out that Obama’s cocaine use extended into his post-college years, longer than Obama had previously acknowledged. And he suggests Obama deployed religion for political purposes; while campaigning for the U.S. Senate, Garrow notes, Obama began toting around a Bible and exhibited “a greater religious faith than close acquaintances had ever previously sensed.”

Throughout the book, Obama displays an almost petulant dissatisfaction with each step he took to reach the Oval Office. Community organizing is not ambitious enough, he decides, so he goes to law school. But then he moves into politics because “I saw the law as being inadequate to the task “of achieving social change,” Obama explains. In Springfield, he is again disillusioned by “the realization that politics is a business . . . an activity that’s designed to advance one’s career, accumulate resources and help one’s friends,” as “opposed to a mission.”And upon reaching the U.S. Senate, he tells National Journal that he is “surprised by the lack of deliberation in the world’s greatest deliberative body.” Nothing measures up.

“Rising Star” concludes with Obama announcing his presidential campaign, and Garrow speeds through the Obama presidency in a clunky and tacky epilogue, in which he recaps the growing media disenchantment with Obama and goes out of his way to cite unfavorable reviews of earlier Obama biographies. (Come on, David. Other books can be good.) In his acknowledgments, Garrow says that Obama granted him eight hours of off-the-record conversations and even read the bulk of the manuscript. “His understandable remaining disagreements — some strong indeed — with multiple characterizations and interpretations contained herein do not lessen my deep thankfulness for his appreciation of the scholarly seriousness with which I have pursued this project,” Garrow writes.

That is Obama now: a scholarly project, a figure of history. After the eight years of his presidency, it is odd to consider him in the past tense. Yes, he remains a public figure, as the mini-controversy over his speaking fees shows, and he is not going away, and certainly not with a post-presidential memoir still coming. But now he is fighting for history and legacy, and one of those battles is against another figure whose ascent is even more bizarre, yet perhaps no less personally preordained.

Obama had considered Donald Trump long before either man won the presidency, and brushed off his existence as a misguided national fantasy. Americans have a “continuing normative commitment to the ideals of individual freedom and mobility,” Obama wrote in the old Harvard book manuscript, now more than 25 years old. “The depth of this commitment may be summarily dismissed as the unfounded optimism of the average American — I may not be Donald Trump now, but just you wait; if I don’t make it, my children will.”