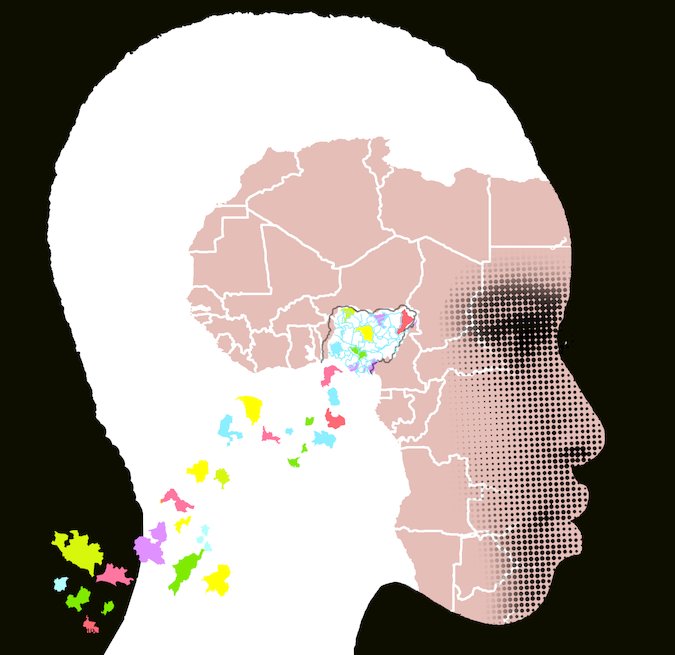

Forty-six years ago this month, Nigeria’s civil war came to an end with the surrender of the secessionist Republic of Biafra. The two and a half years of fighting took some two million lives, but when the bitter conflict ended the triumphant Nigerian government proclaimed, “No Victor, No Vanquished.” Nevertheless, the discontent of the ethnic Igbo people of southeast Nigeria lingers on.

In 1999, a group known as the Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra emerged, seeking through protests and political agitation to re-establish an independent nation. In recent years it has been overshadowed by another group, the Indigenous People of Biafra, which also calls for independence, by violence if necessary.

Led by Nnamdi Kanu, a Nigerian who was living in Britain until last October, it has demonstrated greater sophistication than Massob. Its main publicity tool is Radio Biafra, an online station that spreads the call for “liberation” and “self-emancipation” from the “zoo” called Nigeria. These activities have annoyed President Muhammadu Buhari, who has publicly backed Mr. Kanu’s ongoing trial for treason.

When the Biafran War broke out in 1967 in the wake of widespread communal violence, Lieut. Col. Odumegwu Ojukwu, a leading Igbo officer, declared that “eastern Nigerians are no longer wanted as equal partners in the Federation of Nigeria.” That feeling is still widely shared among the Igbo. But the frustrations of today’s would-be Biafrans are no different from those of their neighbors in the Niger Delta, whose oil keeps Nigeria going but gets them little in return, apart from gas fires and oil spills. Nor do they differ from the grievances of their fellow countrymen in the north, who continue to wallow in levels of illiteracy and poverty that make the south seem prosperous in comparison.

The reality is that no part of Nigeria has a monopoly on victimhood. The impulse to protest suffering and to seek to determine one’s destiny is not wrongheaded; the problem lies in seeking change in a manner that incites ethnic hatred and violence. It would be better for Biafran separatists to drop their calls for independence and push instead for constitutional change that would strengthen the federal system Nigeria purports to practice. Our current Constitution, like the others that followed independence from Britain in 1960, is the product of military leaders whose agenda has rarely coincided with the public good. Though it opens with the requisite words (“We the people of the Federal Republic of Nigeria … ”), it was crafted by a handpicked committee and not made public until the military transferred power to the civilian government on May 29, 1999.

Igbo separatists would also do better to follow the example of Scotland and push for a referendum to decide the future of the region. Admittedly, the central government would be unlikely to endorse such a call for fear that it might trigger an avalanche of referendum requests in this country of more than 250 ethnic groups. But were one to take place, my guess is that it would turn out overwhelmingly in favor of preserving union with Nigeria.

There will never be enough support in the southeast for independence from Nigeria, mainly because most of the people there realize that there would be little to gain and much to lose. It’s doubtful that the delta’s several minority ethnic groups share the conviction of the Biafran agitators that the oil-rich delta states are a natural part of Biafra. Without the Niger delta, Biafra would be a tiny, landlocked nation, its enterprising people hobbled by a requirement to obtain visas to do business in places where they’ve lived and traded in for decades.

Moreover, an independent Biafra would remain riven along the very tribal and religious lines that are being invoked to justify its leaving Nigeria. It’s easy for the Igbo to regard themselves as a cultural and religious monolith as long as they remain in Nigeria. But all Nigerians should know that there is no end to subdividing ourselves, once we give in to the impulse. In an independent, overwhelmingly Christian Biafra, people would begin to identify themselves as Anglicans and Catholics and Methodists — as they already sometimes do in local politics. In the run-up to last year’s elections, for example, Anglican bishops warned the ruling party in the Igbo state of Enugu that they would not accept a gubernatorial ticket composed entirely of Catholic candidates. The party disregarded the warning.

The clamor for a referendum would provide a great opportunity for those like me who believe (to take a phrase from British opponents of Scottish independence) that Nigeria would be “Better Together.” Admittedly it’s hard to see this in a country where online comments routinely degenerate into ethnic sniping, but in fact Nigeria’s diversity could, with proper framing, be turned into a unifying motif.

That “Better Together” campaign would require much soul searching about our country’s painful past. It would also involve recognizing the complaints of the many Igbo voices who are weary of marginalization but do not support the idea of secession.

Almost every day since Mr. Kanu’s arrest, there have been protests and calls for the government to free him. In handling his case, the government needs to tread carefully, ensuring that it does not transform him into a cause célèbre.

A few weeks ago, Nigerian newspapers reported the existence of a handwritten statement Mr. Kanu submitted to law enforcement agents shortly after his arrest, in which he apologized “unreservedly” for the “regrettable” and “uncomplimentary things” he had said about President Buhari and some other people. The government should consider capitalizing on this hint of remorse and making an offer of amnesty to Mr. Kanu in exchange for a pledge to be less-disruptive in his approach.

The best way for the government to permanently sideline those who call for political violence is to push for the economic reforms that President Buhari has vowed to accomplish. Tackling corruption and ensuring more equitable distribution of Nigeria’s wealth will benefit all its people. Splintering the country into a hodgepodge of independent states will not.

Tolu Ogunlesi is a journalist, communications consultant, and the author, most recently, of the novella, “Conquest & Conviviality.”