On July 6, 1967, civil war broke out in Nigeria between the country’s military and the forces of Biafra, an independent republic proclaimed by ex-Nigerian military officer Odumegwu Ojukwu on May 30 of that year. The war killed more than 1 million people, many of whom died from starvation. It ended in January 1970 with the reintegration of Biafra into Nigeria.

Malnutrition, Red Cross, kwashiorkor, relief flights, genocide, the Uli airstrip used by Biafran planes to elude the Nigerian blockade, mercenaries, the Aburi accord that broke down and led to war—these are some of the memory triggers of the Nigerian civil war of secession that we would like to re-assign.

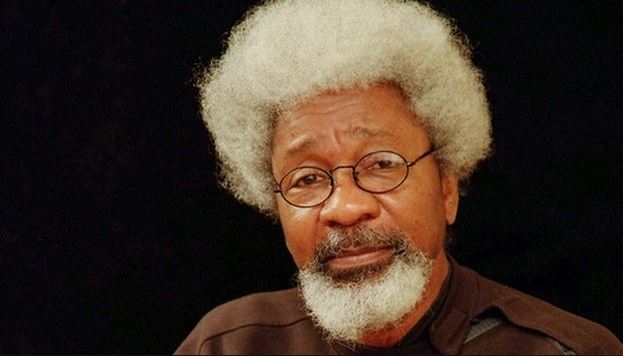

Over a million lives perished—a shameful proportion of them children—mostly through starvation and aerial bombardment. The Nigerian federal government, committed to the doctrine of oneness, had boasted that the conflict would last no longer than three weeks of “police action.” We had learnt much from the politics of other nations, but apparently not from history; the war lasted more than two years. Noble Laureate, Prof Wole Soyika Tormented by the image of a herd of human lemmings rushing to their doom, as a young writer, I made the “treasonable” statement warning that the secessionist state, Biafra, could never be defeated.

The simplistic rendition of that conviction in most minds—certainly in the minds of the then-ruling military and its elite support—was that this applied merely to the physical field of combat. Thus it was regarded as a psychological offensive against the federal side, an attempt to demoralize its soldiers while boosting the war spirit of the enemy. That “enemy” had also boasted that no force in black Africa could defeat them.

My visit to the Biafran enclave in October 1966 resulted in arrest and detention. During interrogation, I insisted that my statement was meant as a counter to the surge of emotive nationalism and a slavish sanctification of colonial boundaries. Biafra was therefore an expression of that rejection and its replacement with a people’s self-constitutive rights.

This specific challenge owed its genesis to memory at its rawest, the memory of ethnic cleansing, whose remedy could not be sought rationally in a campaign of subjugation against an already traumatized community.

One question, rhetorical in tone, stuck in my mind for long afterwards. It went thus: “Why should you take it on yourself to make such a statement? Is it because you’re a writer? Who are you to take a contrary stance to the government?” I replied to myself that I had learned to listen. The young man countered that he was on the side of history, and Biafra would be crushed. Not quite, as it turned out. The Biafrans were indeed defeated on the battlefield, but crushed?

Today, most Nigerians know better. Biafra has not been defeated. If anyone was left in any doubt about this, the last work of my late colleague, Chinua Achebe’s There Was A Country, has left us re-thinking. New generation writers, born long after that brutal war, have inherited and continue to propagate the Biafran doctrine, an article of faith among the Igbo populace, even among those who pay lip-service to a united nation.

Millions remain sworn to uphold it. Many have died at the hands of the police and the military as succeeding guardians of that legacy troop out to reclaim it in defiant manifestations. Amnesty International estimated that at least 150 pro-Biafra activists have been killed since August 2015. Some of their leaders, including the director of their official mouthpiece, Radio Biafra, remain on trial for alleged subversion and treason. Others have gone underground.

The war is not over, only the tactics have changed. One could claim that a project of internal secession is unfolding, one that skirts the peripheries of Nigerian laws, testing what they permit, and daring what they do not. As for the victorious side, analysts continue to cite the lingering consequences of the war of secession among the main causes of the nation’s instability, alongside contemporary factors such as mismanagement of petroleum resources, corruption, visionless leadership, etc. Today, secession simmers openly, and is moving steadily beyond rhetoric. It has already taken on a dangerous complement—ejection.

A number of combative youth organizations in the northern part of Nigeria recently called for the expulsion of the Igbo from their lands for daring once again to talk about secession. Mainstream leaders have disowned them, but some support has been voiced by individuals within the same adult cadre, including its intelligentsia. Debate is intense, often acrimonious.

Sadly however, one is left with a feeling that most participants in this discourse shy away from a fundamental component of nation being, one that transcends the Biafran will to corporate existence. That principle virtually gasps for air under the wishfully terminal mantra that goes: “The unity of Nigeria is non-negotiable.” I have never understood how this is supposed to differ from the dogma of certain religious strains that declare conversion from faith to be an act of apostasy, punishable by death. Nationality, like religion, is only another construct into which one is either born, or acquires by accident or indoctrination.

Those who insist on the divine right of nation over a people’s choice seem unaware that they box themselves into the same doctrinaire mould of mere habit, just like religion. In the Nigerian instance, however, the matter is even more troubling. Since the absolutists of nation indivisibility are not ignorant of the histories of other nations and are immersed daily under evidence of the assertive factor of negotiation—be it in the language of arms and violence or the conference table—since they know full well that this process straddles pre-colonial, colonial and postcolonial histories, such speakers unconsciously imply that Africans are sub-citizens of the real world and are not entitled to make their own choices, even in this modern age. This smacks of an inferiority complex, if not of a slavish indoctrination, when we additionally consider how today’s Africa came to be, a land mass of constitutive units that were largely determined by alien interests, and thus, hold possibilities of fatal flaws.

Also requiring contestation is the implicit equation of supreme sacrifice with supreme entitlement: Those who say, “We have shed our blood for Nigerian unity, and will not stand by and watch it dismantled.” My observation is that in civil warfare—indeed in most kinds of warfare—civilians pay the higher price in lives, possessions and dignity. We need therefore to eliminate the distracting lament of professionals of violence and confront, in its own right, the issue of the collective volition of any human grouping. This leaves us with the other line of approach, the line of frankly subjective or reasoned, pragmatic preferences. It is a positioning that admits, quite simply, I am a creature of habit and prefer things as they are. Or: I like to be a big frog in a small pond, and allied determinants. Such individual and collective preferences for nation validation offer sincere basis for negotiation and resolution.

Once conceded, we proceed to invoke the positives of cohabitation that render fragmentation mostly adventurist and potentially destructive. Habit is a great motivator, but it should not be permitted to transform itself into categorical controls that make any existing condition “non-negotiable.” Independence surely means more the severance of ties with an imperial order. It need not go so far as to dictate the dismantling of its bequests but certainly leaves open the option of placing it in question. Propagators of the inflexible “nationalist” line unabashedly attempt to shut down this questioning.

They distort even the stance of those whose preference is that the nation remain one, but base their pleading strictly on a pragmatic platform, not as the manifestation of a divine will. The unity of any nation is not only historically subject to negotiation; nation is itself an offspring of negotiation. So what is so exceptional about those who inhabit the Nigerian nation space? Nothing. Except we wish to situate them outside history. Should Biafra stay in, or opt out of Nigeria? That is the latent question. Even after years of turbulent co-tenancy, it seems unreal to conceive of a Nigeria without Biafra. My preference for “in” goes beyond objective assessment of economic, cultural and social advantages for Biafra and the rest of us.

Today’s global realities make multi-textured nations far more compelling, not only for outside investors—tourists included—but equally inspiring to the occupants of any nation space. The West African region is marked by an intersection of horizontally and vertically-formed groupings and identities, the result of colonial intervention in the race for territory. The result has proved often dispiriting but just as often stimulating. It has gone on for long, with developmental structures whose dismantling strikes one as being potentially perilous even for the most resilient and endowed of the resultant pieces. Among many analogies, I have heard and read Nigeria described as a ticking time-bomb.

Ironically, I see in this very fear a strong argument for remaining intact. An explosion in closed space is deadlier than in a wider arena which stands a chance of diffusing the impact and enabling survival. My preference for remaining one is thus reinforced by that very doomsday prediction, not by any presumptive law of human association.

Among the lessons learnt today is that changing the content of geography texts does not obliterate the fundamental attachment to an idea. The Bight of Biafra was renamed during the civil war—to expunge the secessionist consciousness—but that ruse has clearly failed. Orders from a section of Igbo leadership for restoration of the original name is a warning that the Biafran narrative has not ended. When added to the widely spread observance earlier this year of sit-at-home protests to mark Biafra Day on May 30, it would be wise to respond with a fresh understanding to the pulsation of the new Biafran generation.

Wole Soyinka is a Nigerian playwright and poet who was awarded the 1986 Nobel Prize in Literature.