Nicholas Boston – City University of New York

Among the hundreds of thousands of patriots that Poland celebrates for serving in the resistance movement in World War Two there is one black, Nigeria-born man.

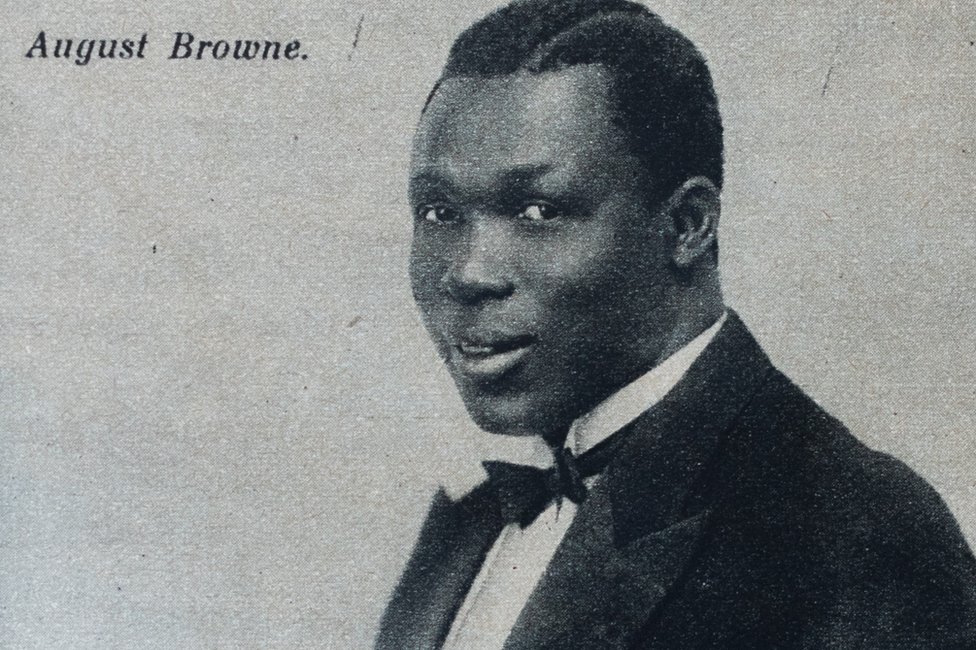

Jazz musician August Agboola Browne was in his forties, and had been in Poland for 17 years, when he joined the struggle against Nazi occupation in 1939 – thought to be the only black person in the country to do so.

Under the code name “Ali”, he fought for his adopted country during the Siege of Warsaw when Germany invaded, and later in the Warsaw Uprising, which ended 76 years ago this month.

Astoundingly, he survived the war in which 94% of the residents of Poland’s capital were either killed or displaced, and continued living in the ravaged city until 1956 when he emigrated with his second wife to Britain.

A small stone monument in Warsaw now commemorates Browne’s life. But the scant details that there are may never have been known were it not for an application he made to join a veterans’ association in 1949.

The document was filed away for six decades, until 2009, when Zbigniew Osinski from the Warsaw Rising Museum came across it.

This form, filled out in beautiful cursive handwriting and with a passport-style photo attached to one corner, is his Rosetta Stone – the documentary fragment that led researchers to interpret isolated facts about his life and locate living descendants.

In the picture, Browne, dressed in a jacket and a snugly fitting jumper, looks lively and youthful with a hint of a smile on his face. All who met Browne described him as a handsome man and a sharp dresser.

By this time he was in his fifties, as the form reveals that he was born on 22 July 1895 to Wallace and Jozefina in Lagos – then part of the British Empire.

He arrived in England aboard a British merchant ship with his longshoreman father. From there, he joined a theatre troupe touring Europe and ended up in Poland via Germany.

‘Sheltered ghetto refugees’

Frustratingly, the form does not say what inspired him to leave Nigeria, or make Poland his destination, so an adventurous spirit seems the likeliest explanation. But by the 1930s, he became a celebrated jazz percussionist playing in Warsaw’s restaurants.

What Browne did write was that in the resistance he distributed underground newspapers, traded electronic equipment and “sheltered refugees from the ghetto”. This was a sealed-off area of the city in which Jews were forced by the Nazis to live and where 91,000 died from starvation, disease and murder. Some 300,000 were transported to their deaths in Nazi concentration camps.

Warsaw Uprising

August-October 1944

- The Polish underground, known as the Home Army, attacked the German occupying forces on 1 August

- They swiftly gained control of much of the city

- Germany sent reinforcements and the nearby Soviet army did not help

- The Poles surrendered on 2 October after 63 days

- 200,000 civilians and 16,000 Polish fighters died

Source: Encyclopaedia Britannica and Warsaw Rising Museum

It appears that for Browne, staying in Poland after the war was a choice – as a citizen of the British Empire, he had the opportunity to leave.

When he arrived in Poland, he first settled in Krakow where he married his first wife, Zofia Pykowna, with whom he had two sons, Ryszard and Aleksander.

The marriage failed but at the outbreak of the war, Browne arranged for his children and their mother to seek refuge in England. But – perhaps committed to the Polish struggle – Browne did not go with them.

The incomplete jigsaw of information gives rise to many questions about his life.

‘A quiet, private man’

Tatiana Browne, his daughter from his second, much longer, marriage to Olga Miechowicz, was born and brought up in London and is his only surviving child in Britain. She says he never talked about what had happened to him.

She is now 62 – her father died in 1976 when she was 17. She remembers him as “very quiet, very private, and quite distant” and that he never discussed his background in Poland or his early years in Lagos.

Tatiana is not certain why neither of her parents told her much about their past. She suspects it was to bury the trauma they endured and atrocities they witnessed.

Thinking back, she recalls watching a documentary about the war with her parents and her mother saying: “I remember seeing people being hanged in the streets; I know that’s true because I saw it with my own eyes.”

But there was no discussion and now she wishes they had told her more.

Browne, though, never turned his back on the Polish culture that he had lived in for almost 35 years, and Tatiana says that Polish was the only language spoken in their London home.

He was remembered by an acquaintance in Poland for speaking “the purest Polish language, even with a Warsaw accent”. He was fluent in several languages.

“Dad taught me how to read and write in English,” Tatiana says.

‘Quick wit and real charm’

How the musician, who as a black person would have been so conspicuous, was able to survive in Nazi-occupied Poland remains a mystery.

Two other African men, Jozef Diak from Senegal, and Sam Sandi, whose exact place of origin on the continent is unclear, had served in the Polish army during the Polish-Bolshevik War (1919-1921) and remained in Warsaw afterwards, but both died before World War Two began.

Discounting them and Browne, experts say there may have been two other black Warsaw residents in the interwar years, professional entertainers whose traces disappear during the occupation.

But Tatiana’s recollection of her father’s charismatic personality may give a clue to his own endurance.

“Dad had a real quick wit and a real charm about him,” Tatiana says.

“When we used to go to church on a Sunday, I used to see him interact with other people. He had a real warmth that drew you in so you automatically liked him.

“When he was in company with other people, there was just this [energy]. People were drawn to him.”

Browne’s story emerged in 2009 at a time of heightened patriotism and xenophobia in Poland.

It drew immediate interest from across the political spectrum and there were calls to memorialise him as a national hero.

At that time, then-President Lech Kaczynski, co-founder of the conservative Law and Justice party, wanted to “honour him on the occasion of the 65th anniversary of the Warsaw Uprising”, said Krzysztof Karpinski, a jazz historian who served as vice-president of the Polish Jazz Association, which was contacted by Kaczynski’s office for more information about Browne.

But Kaczynski died in a plane crash in 2010 and the plan apparently went with him.

It was not until last year that a small monument to the Nigerian-Polish resistance fighter was finally unveiled. That was funded by a non-profit organisation, the Freedom and Peace Movement Foundation. His war service is honoured by conservatives and progressives alike to symbolise the Poland of today.

Browne led a modest existence in England for the last two decades of his life. He continued working as a musician, at first doing session work. When he got older, “we had a piano at home so he used to give piano lessons”, Tatiana says.

They were a “lovely family”, Dr Michael Modell, who treated Browne for cancer, remembers.

He died at the age of 81 in 1976 and is buried under a plain headstone in a north London cemetery.

There is no sign of the traumatic and tumultuous events that he had been part of, which reflects the way he apparently lived his life in London.

“To me, it was just me growing up at home with a mum and dad. Whatever our life was, it was my normal,” Tatiana says.

Nicholas Boston, PhD, is associate professor of media studies at the City University of New York, Lehman College. He was assisted by Wojciech Załuski in Poland.

Credit: BBC