In more than a decade as a Catholic priest in the United States, Martins Emeh has served as a pastor, a cannon law instructor, a diocesan archivist and a judge on the church’s Ecclesiastical Court of Appeals.

Emeh, who came to the United States for graduate school in 1998 from Nigeria and was ordained thereafter, currently serves as a priest at the Epiphany of the Lord Catholic Community, a bustling church in suburban Houston.

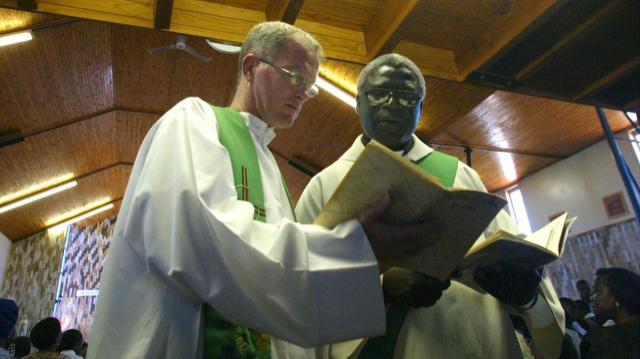

Emeh is part of a growing trend in the Catholic Church in America: a rising number of African-born priests. The number of American-born priests has dropped dramatically in the course of the last 50 years, and foreign born priests are increasingly becoming an important part of the fabric of the Catholic church in America.

No one officially tracks how many African priests work in the States. But Emeh, who served as president of the African Conference of Catholic Clergy and Religious in the United States until 2013, says that as the organization had about 300 member priests at the time with about 80% of them were Nigerians. He estimates there were about 700 African priests in the country and believes the number is much higher today. While the overwhelming majority are Nigerians there are also a few priests of from countries including Ghana, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda and Cameroon.

Catholicism is growing faster in Africa than in any region in the world. In 1910, there were approximately 1 million Catholics in Africa. Today the continent is home to more than 170 million Catholics or 16% of the faith, according to the Pew Research Center. There are already more Christians in Africa than any other continent and by 2060 six of the countries with the top ten largest Christian populations will be in Africa, up from three in 2015.

Reverse missionaries

And now these priests are doing what their European and North American brethren did for several centuries: taking God’s word to people across the ocean. Again, this has been across Christian denominations but even more so with the pentecostal churches which has seen many African-origin churches expand across the US and the United Kingdom.

Back when he was president, Emeh says, the majority of his Catholic priest colleague had been ordained in Africa. That’s still the case but he’s noticed another trend. “Since then we have had even more come in and get ordained here,” says Emeh. “On June 1, I was in New Orleans for the ordination of a Nigerian. That same day another Nigerian was being ordained for Houston.”

Joanna Okereke, assistant director of cultural diversity in the Church at the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, says this year alone Nigerians made up 3% of the priests ordained in the United States.

Okereke, a nun who also hails from Nigeria, says African priests serve in a wide variety of roles, including as vicars, chaplains, university professors and high school teachers.

Patrick Adejo, who was ordained in Nigeria more than two decades ago, is a chaplain at the Veterans Affairs Hospital, a health care facility for former servicemen and women, in Columbia, Missouri.

Adejo, who holds two master’s degrees from universities in Los Angeles and Dayton, Ohio, worked as a chaplain in Nigeria before returning to the U.S. in 2002. He worked as a chaplain at a hospital in Waco, Texas and then helped run a struggling African-American parish at the request of the bishop before joining the Veterans Affairs hospital in 2008.

He says African priests fill a critically important need for the Catholic church in America.

“If we were not here there would be no Sunday mass in many of these parishes and no sacraments,” says Adejo who regularly fills in at parishes in nearby Jefferson City. He believes African priests have received “tremendous acceptance” from lay people.

“They see the impact, the style and the approach to ministry,” he says.

Emeh says African priests have a reputation for being more dedicated, personable, easy going and for regularly making themselves available – even on their days off.

“We don’t look at it simply as a job,” he says.

Bob Bonnott, executive director of the Association of US Catholic priests and a priest for 52 years, says: “The Africans often are younger, kind of dynamic and are joyful and that comes through in spite of language problem or cultural challenges.”

But this trend does not come without challenges.

“Some of them have to deal with the handicap of language in terms of the accent,” says Emeh. “People might complain of not being able to follow especially when they’re speaking rapidly. That becomes a little bit of a handicap in terms of impact.”

Adejo adds that some American priests have the impression that African priests are here for monetary gain.

Then there’s the challenge of racism or at least the perception of it.

“My experience is that people in the community are more accepting than brother priests,” says Emeh. As a seminarian, he had a professor, a nun, who told him she couldn’t understand why an African like him was planning to take up an appointment as a priest in the overwhelmingly white Rockford, Illinois diocese.

“She didn’t believe I was qualified to minister to Caucasians,” he says. “I have worked with many Caucasian priests who have accepted me as a brother. Then I had to deal with some with some who felt threatened when I was sent to study Cannon law. They wondered why I was rising so fast. We’ve had Africans who were priests for many years before they were assigned their own parishes.”

But the bottom line, says Bonnott, is that the presence of African priests is a good thing for the church.

“I think it is expanding Catholic people’s sense that they are a universal church and that we are part of one human race,” he says. “The Catholic faith in Africa is exploding and the seminaries are filled. I think it is a blessing for US Catholics to experience that and relate to this foreign born priests in a mutually enriching way.”