AROUND 140,000 people crowded into St Peter’s Square to hear Pope Francis deliver Christmas mass today, Christmas day. Rome, and by extension Europe, has been the centre of Christianity ever since Emperor Constantine converted to Christianity some 300 years after, according to Christian tradition, Peter, the first pope, arrived there from the Holy Land to spread the gospel and was later crucified. Two millennia later, Christianity is the world’s most popular religion—there are 30% more self-identified Christians in the world than Muslims—and Europe is still the continent with the largest Christian population.

Nonetheless, European priests and ministers are preaching to ever-emptier pews. Just 10% of adults in France and Sweden go to church once a month or more. In Ireland, regular attendance fell from 90% in 1990 to 60% in 2009. Shrinking congregations have led the Church of England, one of Britain’s largest landowners, to close 1,900 churches since 1969, 11% of the total.

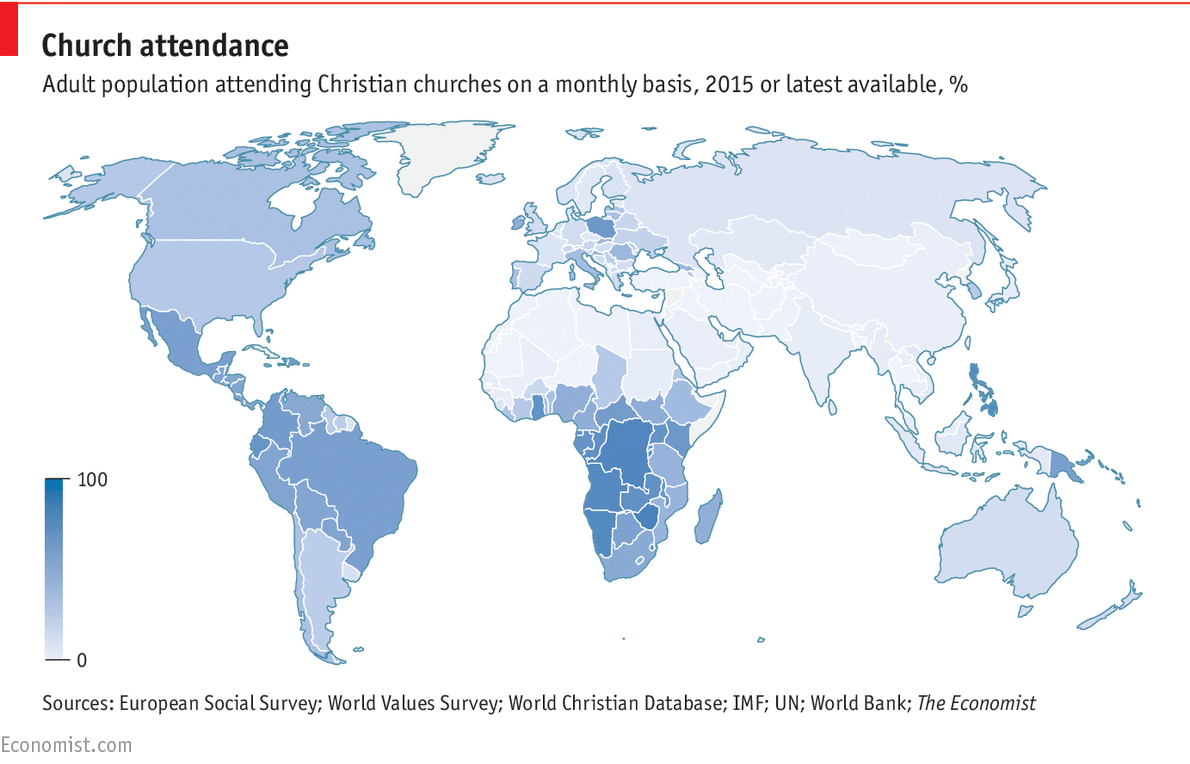

Although immigration has caused the non-Christian share of Europe’s population to rise, the vast majority of the decline in churchgoing stems from creeping secularism, and a trend among the young to favour individual “spirituality” over organised religion. Data from the European Social Survey (ESS), which polled 55,000 Europeans across 29 countries in 2012, show that around a third of Europeans who consider themselves Christian say they attend services once a month or so. Across Europe some 190m people go to church regularly from a nominal Christian population of 585m (see map).

By contrast, sub-Saharan Africans are embracing the gospel with the literal zeal of the converted. According to the Centre for the Study of Global Christianity at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, in 1910 just 9% of the 100m people on the African continent were Christian; today the share is 55% of a population of a billion. Moreover, figures from the World Values Survey (WVS), which covers 86,000 people in 60 countries, indicate they are remarkably devout: across five sub-Saharan African countries for which data are available (Ghana, Nigeria, Rwanda, South Africa and Zimbabwe), 90% of people calling themselves Christian also said they attended church regularly. If those nations are representative of the region as a whole, then perhaps 469m churchgoers now live in Africa. Another 335m or so churchgoing Christians live in Latin America, three-fifths more than in Europe.

Why has Christianity’s centre of gravity shifted south and west? The relationships between church attendance and other survey data provided by the ESS and WVS, along with national-level statistics, offer tantalising clues. One important influence is the dominant strain of Christianity in each region. All else being equal, Orthodox Christians—who do not celebrate Christmas until January 7th—are 14 percentage points less likely to attend church than Catholics, which could be a product of historical antipathy towards religion in the ex-Communist countries where they predominate. The world’s 280m Orthodox Christians reside primarily in Europe. By contrast, evangelicals, who are rare in Europe, are seven percentage points more likely to attend church than Catholics.

Economics also plays an important role. The more affluent a country is, the less frequently its citizens attend church, and western Europe is uniformly rich. On the surface, this pattern makes the United States, in which a healthy 58% of self-identified Christians go to services monthly, hard to explain. However, religious devotion is also strongly associated with concentration of wealth. Holding other factors constant, the odds that an individual will attend church are 15 percentage points higher in the world’s 29 most unequal countries than they are in the most equal ones. And people on the lower rungs of their own country’s economic ladder tend to be more observant than those at the top. America is unusually unequal for a rich country, and its black population is both poorer than the national average and highly devout. Moreover, its immigrants come largely from staunchly Christian Latin America.

Given how improbable the geographic distribution of Christianity today would have appeared 50 or 100 years ago, no one can predict the future shape of the church with any confidence. If economic development and a more equal distribution of income decrease church attendance, then what is good for the world’s poor may be bad for Christianity—Pope Francis might want to be careful what he wishes for. Similarly, people born before 1945 tend to be far more observant than members of subsequent generations. As the elderly faithful die out and are replaced by more secular millennials, churchgoing could decline further.

But demographic trends work against this “peak Christianity” hypothesis. Sub-Saharan Africa is not only home to the world’s most observant Christians; it is also the fastest-growing region on the planet by population. And its entrenched poverty means that even if it enjoys decades of rapid economic development, it is unlikely to reach the levels of wealth that tend to correspond to increased secularisation. As Christians celebrate the birth of Christ, the centre of gravity of the world’s most popular religion is shifting towards the birthplace of humanity itself. Economist