While the British Parliament was debating this week whether to join in airstrikes against ISIS in Syria, one weapon was mentioned repeatedly: Brimstone. In a 36-page report, Prime Minister David Cameron said, “The Brimstone missile which enables us to strike accurately with low collateral damage, therefore increasing the scope for strikes against specific ISIL targets—even the U.S. do not possess this capability.”

Indeed, Brimstone proved itself and its capability against tanks in Libya, to the point that the British paper The Telegraph called it the “British missile envied by the U.S.” But if the Brimstone really is so great, then why doesn’t the US have it?

Hellfire and Brimstone

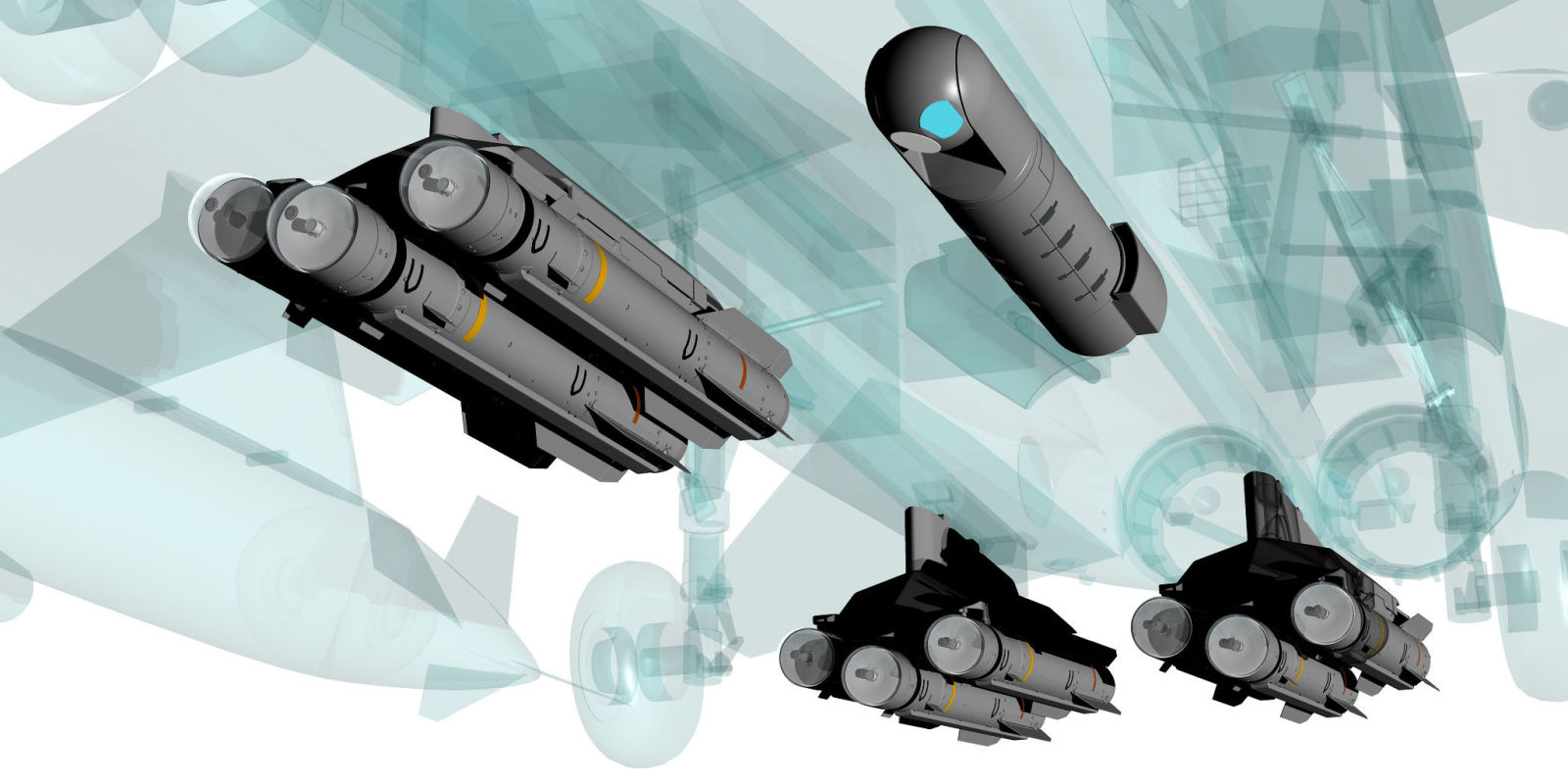

The Brimstone is made by MBDA, a company formed by the merger of several European missile manufacturers in 2001, including the British Matra BAe Dynamics. The missile weighs 116 pounds. It is six feet long and greatly resembles the American Hellfire missile because, as the name might suggest, Brimstone is actually derived from the American weapon. Hellfire and Brimstone—clever, guys.

The story begins back in 1970 with the initial development of the Hellfire anti-tank missile. The previous US Army missile, the TOW, had to be guided by an operator keeping cross-hairs on the target. The HELicopter-Launched FIRE and forget missile—Hellfire, for short—would carry guidance systems that lock on to the target at launch. Unfortunately, the original TV camera-based seeker heads were not satisfactory, and so Hellfire ended up with laser guidance, meaning an operator has to keep a laser dot trained on the target throughout the missile’s flight.

Hellfire is much-loved among American forces, but there was still demand for a true fire-and-forget missile that would find its own way to the target. Brimstone was originally little more than Hellfire with a new seeker, but during the design process the entire missile was rebuilt. Brimstone was based on a millimeter-wave radar, a short wavelength that provides a detailed picture of metal objects. It can identify, track, and lock on to vehicles autonomously. A jet can fly over a formation of enemy vehicles and release several Brimstones to find targets in a single pass. The operator sets a “kill box” for Brimstone, so it will only attack within a given area. In one demonstration, three missiles hit three target vehicles while ignoring nearby neutral vehicles outside the kill box.

This sort of capability might be handy in a WWIII situation against massed tanks, but it is less useful in current wars. Rules of engagement require a human operator in the loop and machines are not permitted to choose their own targets. So Brimstone was upgraded with a second seeker, and the dual-mode Brimstone has laser guidance like the Hellfire alongside the millimeter wave guidance. Either can be used as needed.

Whether Brimstone is any more accurate than Hellfire is a matter of debate. Brimstone can, however, be fired from fast jets, something that Hellfire is not designed for, against targets twelve miles away. It is also claimed to hit targets moving at up to 70 mph using the radar mode. Here it is against test targets at China Lake crossing at up to 50 mph.

As for the Brimstone’s low collateral damage, this is a convenient side-effect of its being designed as an anti-tank missile. The shaped-charge warhead weighs only 14 pounds and is optimized to penetrate armor rather than throwing out shrapnel over a wide area.

When the Hellfire missile (which carries 20 pounds of explosive) was used in Iraq and Afghanistan, the original anti-tank version had limited effectiveness against some targets, so the U.S. designed new versions. The Hellfire K was more effective against personnel, while the M was built to go through a wall or roof before detonating to destroy a building. The latest version, the R or Romeo, combines anti-tank effects with shrapnel and enhanced blast.

THE ROYAL AIR FORCE CANNOT SPARE A BRIMSTONE FOR EVERY TERRORIST IN A TOYOTA.

Basically, Brimstone causes less collateral damage because it causes less damage. However, watching videos of Brimstone in action—destroying a vehicle in Iraq, a turret of an ISIS tank near Ramadi, or a compiltation of death and destruction—makes you appreciate that “low collateral damage” is a relative concept.

The Brimstone is hardly a war-winning silver bullet; a handful of RAF Tornadoes with these missles are unlikely to turn the tide in Syria. While the light weight means that a jet can carry 12 or more Brimstones on a single mission, the weapon costs more than $250,000 per missile. The Royal Air Force cannot spare a Brimstone for every terrorist in a Toyota.

Yet there’s no doubt that Brimstone is useful weapon for attacking precision targets, which leaves us with the question of why the United States doesn’t have them. There is already a millimeter-wave-guided version of the Hellfire for helicopters, and there have long been plans to replace Hellfire with something better, a missile with both laser and radar guidance, capable of being fired from fast jets, just like Brimstone. Unfortunately, the plans have been repeatedly curtailed to pay for other programs. Defense Industry Dailydescribes the project as having “enough missile program cancellations and resurrections to make even Lazarus give up.”

The latest version, known as JAGM, should be here by 2019, with integration on the F-35 by 2021 or so. It may not be a surprise that MDBA is offering Brimstone as a contender for the JAGM program. David Cameron’s new-found enthusiasm for the missile, and its use to support the U.S. effort in Syria, might just help their case.

David Hambling’s new book Swarm Troopers: How small drones will conquer the world is out this month.

Military weapons