Miscarriages, which usually occur as a result of genetic factors and affect 15 to 20 percent of pregnancies, are tragic and very difficult to talk about. A new survey published inObstetrics & Gynecology shows that people harbor many misconceptions about both the frequency and most common causes of miscarriages — misunderstandings that may compound the feelings of guilt and shame that occur in the wake of one.

The researchers, led by Jonah Bardos of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine/Montefiore Medical Center, built a 33-item survey covering many facets of miscarriages and recruited 1,147 respondents via Amazon Mechanical Turk to take it for $.25 each. The authors included some quality-control measures — they note that “if respondents answered the attention check question of ‘I had a fatal heart attack while watching TV’ with a ‘yes’ or ‘maybe,’ meaning they are reporting they have died, all of their responses were excluded from analysis.”

“This is certainly the only study of this size that’s been conducted” on miscarriages, said Dr. Zev Williams, the survey’s corresponding author, “but I actually think this may be the only study that’s ever been done to look at perceptions and understandings of miscarriage.” The respondents were, generally speaking, representative of the U.S. population, except on race — there were comparatively more whites and Asians and fewer Latinos and African-Americans.

The survey revealed that people greatly underestimate the frequency of miscarriages: 55 percent believed they affect less than 6 percent of all pregnancies. And 22 percent wrongly believed “that lifestyle choices such as drug, alcohol, or tobacco use during pregnancy are the single most common cause of miscarriage, more common than genetic or medical causes.” In both cases, men were two and a half times more likely to hold the false belief than women.

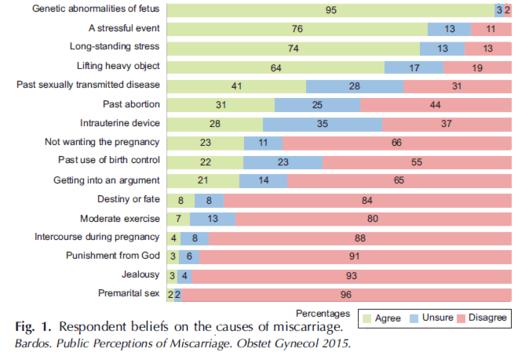

More generally, the respondents exhibited a rather emotionally charged view of the causes of miscarriage:

As the chart indicates, lots of people believe miscarriages are caused by things that 1) don’t actually cause them, like arguing, lifting heavy objects, having had STDs in the past, or having used contraception in the past, and 2) could easily be interpreted, in the wake of a miscarriage, as a woman’s or a couple’s “fault.”

To Williams, some of these beliefs have become entrenched in part because miscarriages are an ancient problem and therefore beliefs about their causes “were generated at a time when our thinking about health was radically different.” These ideas, much like folk remedies, simply get passed down from generation to generation and become difficult to dislodge as a result. The problem is that the one-two punch of people underestimating the frequency of miscarriages and overestimating the likelihood that they’re caused by some failing on the part of a woman or a couple leads to a cycle of stigma. “Because people feel (erroneously) guilty and ashamed that they had a miscarriage, they don’t discuss it,” Williams explained. “This, in turn, makes those who suffer from a miscarriage feel much more isolated and alone, and this just perpetuates the cycle.”

At the moment, said Williams, “Research into miscarriages is woefully underfunded and lags behind other far less common conditions.” But he’s confident that, in the long run, knowledge can help dispel some of the misunderstandings revealed by him and his team’s survey. Just as the taboo surrounding cancer dissipated a bit “once we started to understand the molecular underpinnings of that disease,” he said, “so, too, I think a lot of the myths surrounding miscarriage will go away once we gain a deeper understanding of the true causes.”

Yahoo Health